The human psyche is not univocal, but is comprised of different parts— each with its own set of needs and desires. We can therefore think of the psyche as a community, one in which competing needs are constantly being weighed and negotiated.

In a similar sense, a personality type is a community of functions. These functions play different roles and use different strategies for achieving their goals. And like any community, there are times when the functions are at odds with each other and fail to operate harmoniously. This can engender inner tension that beckons us to reconcile the diverse needs and interests entailed in our type. This tension can arise from ordinary indecision, such as where to eat for lunch, as well as from bigger questions, such as the nature of our life’s purpose. In many cases, our inner dilemmas can be traced back to a set of functions that are struggling to find common ground: should we listen to logic (T) or feelings (F), follow a routine (Si) or explore new possibilities (Ne), etc.?

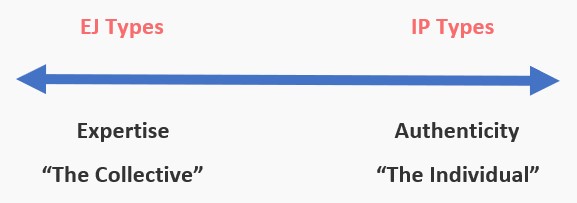

Less commonly discussed, but nevertheless worth examining, is the question of expertise versus personal authenticity / individuality. We might frame this issue as follows:

“Is my primary goal to become & be viewed as an expert?”

-or-

“Is my primary goal to be authentic & express myself as an individual?”

These are questions of identity—of who we strive to become and how we want to be viewed by others. Identity has a personal / introverted component (e.g., What makes me happy? What are my deepest, innermost needs?), as well as a public / extraverted component (e.g., What do I want to be or do with respect to other people / the outside world?)

Notice, this is not an either-or scenario. Regardless of whether we are introverts or extraverts, we all care, to some extent, about both the private and public aspects of our identity. While this makes us more complex and well-rounded individuals, it can also beget tension, anxiety, and indecision as we work to reconcile these competing desires.

Authenticity & Personality Type

We typically associate concerns about authenticity with introverts. In other words, we link authenticity with the private / personal aspect of identity. Although one could just as easily argue that extraverts are acting authentically in adapting themselves to the world (just as introverts work to adapt the world to themselves), the prevailing view of authenticity nevertheless has an introverted bent.

If we dive a little deeper, we learn that authenticity is probably best associated with introverted (I) perceiving (P) types (i.e., “IPs”)—INFP, INTP, ISFP, ISTP—all of who use either Introverted Feeling (Fi) or Introverted Thinking (Ti) as their preferred function. These are the functions of subjectivity and individuality. Namely, Fi and Ti employ independent, subjective judgments and methods to navigate life rather than relying on pre-existing external standards or criteria (EJ).

Now, our non-IP readers may currently be thinking / objecting: “This isn’t fair, I care about individuality and making independent judgments too.” And I’m sure you do. This is because you also use either Ti or Fi, only not as your dominant function. But the fact that a function isn’t dominant doesn’t mean we don’t use it or care about it. Sure, there are times when we get locked into our dominant function to the detriment of everything else, but we can also experience dominant function fatigue which compels us to explore, develop, and honor our other functions. The inferior function can be particularly alluring due to its polarized relationship with the dominant.

That said, if we concede that the dominant function wields the most influence in guiding and shaping our lives, then IPs are the most likely to take an individualized path—the path of artists, philosophers, iconoclasts, small business owners, etc. Moreover, if IPs want their public identity to align with their self-understanding, they will want to be recognized as unique, independent, creative, self-reliant, or some combination thereof.

Expertise & Personality Type

In associating authenticity with IP types, you may have already anticipated that we will link expertise with extraverted (E) judging (J) types (i.e., “EJs”), all of whom employ either Extraverted Feeling (Fe) or Extraverted Thinking (Te) as their dominant function. As discussed in my book, My True Type, both of these functions reference external standards and criteria, whether social / moral (Fe) or rational (Te), for guidance and direction. Unlike Fi and Ti, which derive their operating procedures from within, Fe and Te rely heavily on collective norms, values and methodology.

So what does this have to do with expertise? I contend that just as authenticity is typically construed as an introverted phenomenon, we tend to think of expertise as a sort of collective or extraverted issue. This is particularly obvious with respect to Te matters. What is the first thing we think of when it comes to expertise? Formal education. Thus, those who have earned a doctoral degree, which is essentially a form of Te endorsement (read: “You’ve successfully jumped through all the necessary hoops.”), are already well on their way to expert status. In many cases, we don’t know if such individuals are actually smarter or more educated than those without a degree, since we don’t have the time to scrutinize them all on an individual basis. Instead, we’ve collectively decided to place our trust in institutions, such as universities, to make those determinations for us.

Although Te credentialing is among the most common ways of establishing expertise, or least of opening the door to it, there are alternatives. Emerging thought leaders like Sam Harris and Jordan Peterson, while both having doctoral degrees, are being revered for matters extending well beyond their formal educational background. Sure, Harris is a neuroscientist and Peterson a psychologist, but both are functioning more like philosopher-sages. This brand of expertise, which turns less on formal credentials and more on grassroots support, is a form of Fe endorsement. In other words, if enough people start recognizing someone as an expert or a sage, he or she is, from an Fe perspective, just that.

Again, what Te and Fe have in common is a collective / objective (EJ) emphasis. As far as these functions are concerned, you can’t really be an expert unless some sort of collective body has recognized you as such. Those without collective backing are viewed with suspicion, since trust is something that is built publicly and in some respects quantitatively (i.e., the more followers / credentials / endorsements the better).

While type theory predicts that EJs are most apt to be or strive to become experts, we also know that all types have either Te or Fe somewhere in their function stack. Thus, any type may aspire to expert status, even IP types. In fact, I’ve encountered a striking number of IFPs pursuing doctoral degrees, which might be viewed, psychologically, as an attempt to master their inferior Te.

EJs are generally good at being experts. They play the role well. However, they are rarely as sure of themselves deep down as they appear from without. Even when others readily extol them as experts, in quiet moments alone, EJs may not really believe it. The truth is they often feel out of touch with their inner selves, not knowing who they are apart from their public lives. This may lead some EJs to question, perhaps even relinquish, their expert status in order to discover who they are as individuals (IP). For similar reasons, they may explore various art forms in hopes of discovering their own personal style or voice.

Closing Remarks

Our self-conceptions are not always accurate reflections of who we are or how we operate. Consequently, we can imagine IPs fancying themselves as objective experts while, in actuality, functioning more like individualists. Similarly, we might envision EJs self-identifying as independent thinkers without realizing the degree to which their ideas are being shaped by external forces.

Type theory lends insight into what we might expect from various types based on their respective functions. As individuals, however, we go through phases where we wander away from our dominant function. And because our non-dominant functions can make our lives feel more interesting, novel, or complete, we may even start identifying with them. In fact, infidelity to the dominant function is a common reason people misidentify their type.

Exploring and identifying with our non-dominant functions can have both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, it can spawn growth and development, helping us feel more whole and alive. On the other hand, losing sight of our type’s greatest asset, especially for extended periods of time, is rarely a wise move.

Our ultimate goal, of course, is to experience some sort of merger of authenticity and expertise—a balance between the individual and collective. For IPs, this might involve entertaining and experimenting with established norms and methods, while still granting themselves the final word. For EJs, it might entail making more room for subjectivity and exceptions to the rules, while maintaining a healthy respect for established norms and methods.

We might even consider jettisoning the expertise-authenticity dichotomy altogether and start thinking instead in terms of excellence. If IPs and EJs are making excellent use of their typological strengths and abilities, it doesn’t really matter whether we call them experts or authentic individuals. Either way, they are embodying excellence. And excellence, I suspect, is something we can all value and appreciate, regardless of where we find it.

If you’re looking to clarify your identity, life purpose, career path and more, be sure to check out our online course, Finding Your Path as an INFP, INTP, ENFP or ENTP:

Related Resources:

INTP & INFP Identity-Seekers & Creatives

Changing Faces of Type: Personality Shifts & Identity Crises

My True Type: Clarifying Your Type, Functions & Preferences (book)