I sometimes find myself wondering exactly what it is that we personality junkies value most about typology. What is it about personality typing that seems so important and meaningful? I also reflect on what we’re seeking from personality taxonomies like the Enneagram and the Myers-Briggs. Namely, what is the deeper set of needs and concerns we’re trying to address by engaging with these models?

In their article, A New Big Five, Dan McAdams and Jennifer Pals provide some insight into these concerns, highlighting the centrality of self-narratives in modern life:

Over the past two decades, the concept of narrative has emerged as a new root metaphor in psychology and the social sciences. Narrative approaches to personality suggest that human beings construe their lives as ongoing stories and these life stories help to shape behavior, establish identity, and integrate individuals into modern social life.

Likewise, in a paper called The Three Meanings of Meaning in Life, Frank Martela and Michael Steger contend that a key aspect of life meaning is a sense of coherence. According to the authors, coherence is the cognitive element of meaning-making, an attempt to “make sense” of our life experiences. For most of us, this is achieved by way of self-narratives, by weaving together the diverse strands of our life into a meaningful whole.

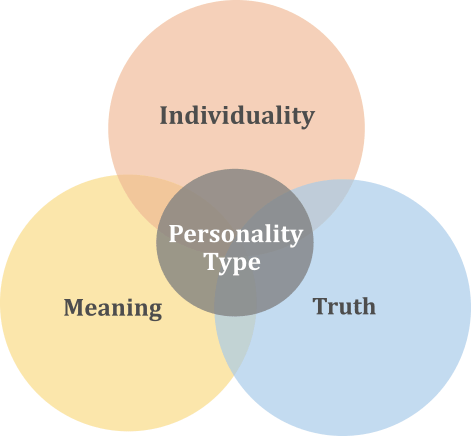

Considering the instrumental role of narratives in crafting and maintaining a modern identity, I’m inclined to argue that we value personality typology, at least in part, because it helps us fashion more coherent and meaningful self-stories. Sure, typology is not the only route to finding identity and purpose in life. For many people, things like family, religion, politics, and work serve as cornerstones of identity. While personality junkies invariably draw on some of these things as well, there must be something unique about their beliefs and values that draws them to typology. In this post, we will discuss three core values shared by type enthusiasts—individuality, truth and meaning—which I see as fueling their interest in self-discovery and personality studies.

Individuality

Few would doubt that we live in an age of individuality and individualism. No longer are our destinies predetermined by the family, religion or culture we are born into. Nor are we guaranteed a meaningful worldview or narrative to embrace as our own. Science, in tandem with various form criticism, have cast doubt on religion as the most trustworthy guide to understanding ourselves and our origins. The decision-making onus with respect to our life path and worldview has thus shifted from culture to the individual.

A foremost challenge of individuality, which I’ve discussed elsewhere, is the problem of choice. Namely, the difficulty of making decisions in a world teeming with options and possibilities. At times, we may even find ourselves yearning for bygone eras, times when life was simpler and choices fewer.

Individualism can also have a fragmenting effect, both socially and psychologically. It’s partly this sense of fragmentation that inspires our search for coherence by way of self-narratives. Of course, achieving and maintaining a coherent self-understanding is easier said than done. Weaving together an identity requires time and investment, and it’s a project that’s in many respects never finished, especially for those intent on living life to the fullest.

Truth

It’s hard to deny the foundational role of science in modern life, both practically and intellectually. Science has admonished us to value and strive for objective truth in our beliefs and life choices. To some extent, this includes understanding ourselves more objectively. Not only is this practically advantageous (e.g., knowing whether one is better suited to study physics versus nursing), but confers a sense of alignment with truth as a core value. If science is one of the few “universals” to which we can all assent, then striving for truth can engender a sense of solidarity and common purpose which, in our age of individualism, is hard to come by.

A corollary of valuing truth is we don’t want our self-narratives to be comprised of mere fictions. While our ability to obtain objective self-knowledge is admittedly far from perfect, we can still hold it as an animating ideal. We can also achieve greater objectivity by employing personality taxonomies with a scientific basis, such as the Myers-Briggs and Big Five. The further we stray from empirical science (e.g., astrology), the more our beliefs are shaped by confirmation bias and other psychological mirages which feign (and ultimately undermine) objectivity.

Another advantage of science-based typological frameworks is they help us conceptualize and integrate different parts of ourselves into a more economical and coherent self-view. As we saw earlier, it’s important to discern unifying themes for ourselves and our lives. Personality theories can help us make sense of what might otherwise seem to be disparate or unrelated parts of ourselves.

Meaning

Whatever the importance of an objective self-understanding, part of composing a self-narrative is imagining ourselves into the future, that is, having a sense of where we’re headed. Indeed, part and parcel of being a self is becoming a self, developing and expanding into new territories. This requires some measure of imagination, or at least a willingness to embrace and emulate certain ideals or role models.

Personality types can prove useful here as well, especially when personified into general roles or archetypes (e.g., Investigator, Artist, Explorer). As Jung noted in “The Archetypes and Collective Unconscious,” archetypes are “among the highest values of the human psyche.” Moreover, if these archetypes “remain conscious in some form or another, the energy that belongs to them can flow freely.” Further, Jung observed that in maintaining contact with archetypes, “the rational is counterbalanced by the irrational.”

Balancing the rational (e.g., truth / objectivity) with the irrational (e.g., a sense of meaning / beauty) is the hallmark of a useful and meaningful typology. According to Jung, “in the role of absolute tyrant it [rationality] has no meaning.” However, if we swing too far in the opposite direction, we are left with sheer relativism, a world devoid of agreed upon standards for determining truth.

This leads to the question of which personality taxonomy is best suited for the task of unifying truth and meaning. With regard to the former, the Big Five taxonomy is the closest thing we have to scientific consensus and the Myers-Briggs, in light of its considerable overlaps with the Big Five, is not far off. Questions of meaning and beauty are harder to answer scientifically, although popular appeal may give us some insight into what people value. In this respect, the Myers-Briggs is arguably still the most popular taxonomy worldwide, although the Enneagram has gained some ground in recent years.

If you’re seeking to better understand yourself, your personality, and your path in life, be sure to explore four books as well as our online course:

Finding Your Path as an INFP, INTP, ENFP or ENTP

Read More:

The Introvert’s Quest for Identity & Vocation

Ginny Kreeft says

Thank you for this post. So helpful in understanding the value of truth and meaning.

A.J. Drenth says

You’re welcome Ginny. Thanks for your comment.

Adele says

Always so appreciate your thoughtful articles digging deeper into personality.

This comment brought pause: “The further we stray from empirical science (e.g., astrology), the more our beliefs are shaped by confirmation bias and other psychological mirages which feign (and ultimately undermine) objectivity.”

Another challenge I see unfolding within the field of science is one of political bias — where not only papers, but people, are being shut out because they don’t match the current academic political climate . . . creating more mirages that feign objectivity.