Students of psychology are probably familiar with the verbal vs. visual cognitive style dichotomy, which suggests that individuals tend to prefer either language-oriented or image-oriented cognition. This notion was originally based on research that associated language with the left side of the brain and visual processing with the right hemisphere. Hence, “left-brained” types were considered more verbal and “right-brained” types more visual.

As I was contemplating this verbal-visual dichotomy, it struck me that our first interactions with the world, irrespective of cognitive style, are predominantly visual in nature. Simply put, we all start out as visual processors (those with congenital blindness being the obvious exception). Of course, this doesn’t mean that infants are conjuring clear mental images in the manner of an artist or architect. They do, however, rely heavily on visual input to orient themselves as they work to construct an understanding of the world around them.

Although we all begin life as visual learners, research has demonstrated that we aren’t all attending to the same things. And any psychologist worth her salt would tell you that what we pay attention to matters insofar as it shapes the trajectory of our neuropsychological development.

In this post, we will examine early play and visual proclivities among infants and toddlers, including how they relate to gender and the Myers-Briggs thinking (T) – feeling (F) dichotomy. These early preferences can be seen as laying the groundwork for adult cognitive styles—visual, spatial and verbal—each of which we will discuss in detail. We will conclude by exploring the relationships between ability, cognitive style and personality type.

Early Visual & Play Preferences

In order to understand what infants and toddlers are paying attention to, psychology researchers are now using eye-tracking technologies that help reduce subjective bias. One thing they’ve discovered is that, even as infants, females tend to express more interest in and will gaze longer at human faces, whereas males spend less time on faces and more tracking moving objects.

Moreover, as early as age two, girls show greater interest in objects representing people (e.g., dolls), while boys prefer toys representing tools or vehicles. Researchers believe that the early manifestation of these differences suggests they are innate rather than learned.

Extrapolating from these observations, we can see how imaginative doll play might aid in the development of emotional and social intelligence, perhaps even more so if done with other people. Likewise, consistent interactions with tools, truck, blocks, balls, etc. might foster the development of spatial and mechanical reasoning skills.

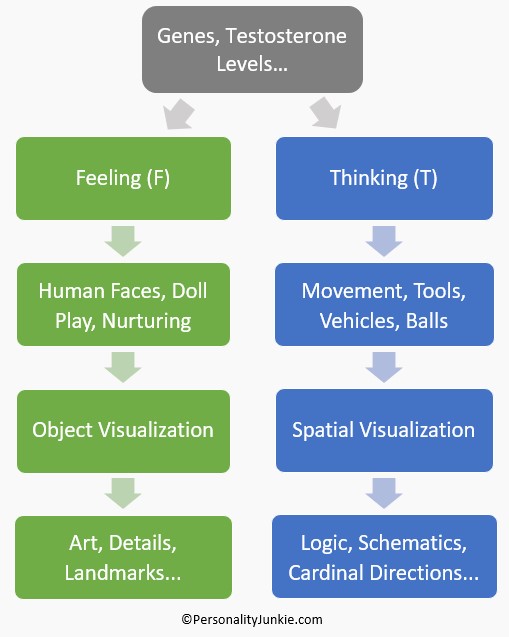

Beyond these general gender trends, testosterone levels have been shown to significantly impact the preferences and behavior of young children. In one study, girls with higher testosterone levels played more frequently with toy vehicles than other girls did, while lower-testosterone boys interacted more with dolls than other boys tended to. This suggests that testosterone levels affect play interests in both sexes.

If we tie this to personality type, early play interests are likely indicators of a child’s thinking (T) vs. feeling (F) preference. Namely, attention to faces, engaging in doll play, nurturing behavior, and attunement to human / social dynamics are consistent with a preference for feeling. By contrast, interest in toy guns, blocks, vehicles, tools, etc. is suggestive of a thinking orientation.

Female thinkers or male feelers may be less polarized and exhibit more mixed interests, but their T-F preference is typically still identifiable. Although girls who grow up around boys may consider themselves “tomboys,” this sometimes arises out of social concerns, such as wanting to fit in, rather than a deep-seated interest in T activities. Hence, early play preferences (e.g., ages 2-4) may offer a more accurate picture of a child’s T-F preference.

Adult Cognitive Styles: Visual, Spatial & Verbal

Earlier, I mentioned the commonly held verbal-visual cognitive style dichotomy. I then made the case that, at least early in life, we are all predominantly visual.

Recent studies conducted by a Harvard researcher, Maria Kozhevnikov, have shown the verbal-visual distinction to be incomplete. According to Kozhevnikov, there are actually two distinct visual styles. The first, object visualization, involves seeing or recalling mental images of objects / scenes with full color, vividness, and detail. The second type, spatial visualization, emphasizes visual features like location, movement, spatial relations and other spatial attributes. The mental imagery of spatial visualizers often omits many of an object’s details in favor of its general contours.

To help individuals identify their preferred mode of visual processing, Kozhevnikov and her colleague, Olesya Blazhenkova, developed the Object-Spatial Imagery Questionnaire (OSIQ). Here are a few of the questionnaire’s items:

Object Visualization Items:

- My images are very colorful and bright.

- When reading fiction, I usually form a clear and detailed mental picture of the scene being described.

- I remember everything visually. I can recount what people wore…

Spatial Visualization Items:

- I prefer schematic diagrams and sketches when reading a textbook.

- I can easily imagine and mentally rotate 3-D geometric figures.

- I can easily sketch a blueprint for a building I’m familiar with.

A person’s preference for navigating by landmarks versus cardinal directions also seems relevant here. Namely, we would expect object visualizers to rely more on landmarks and spatial visualizers on cardinal directions. Research seems to point in this direction, as spatial reasoning ability and self-reported sense of direction (i.e., “wayfinding”) have shown to be correlated.

Studies also indicate that males tend to perform better on spatial reasoning tests and identify as spatial visualizers, while females are more apt to prefer and excel at object visualization. Moreover, research suggests that women, on average, are better at remembering faces than men are. This fits with their proclivity for object visualization, as facial recognition is surely aided by attention to color, shading and other visual details.

The following diagram illustrates how the researching findings we’ve reviewed are interrelated and align with either feeling or thinking:

What about “Verbal People?”

Those of you who don’t experience a lot of mental imagery may have a hard time self-identifying as either an object visualizer or a spatial visualizer. Instead, you might fancy yourself a “verbal” person. While the visual-verbal distinction has a certain utility, it’s also true that language is in many respects fashioned on our visual observations. So even individuals who “think in words” are reliant on subconscious imagery. After all, if much of what we learn about human (F) or physical (T) phenomena comes by way of visual observation, it stands to reason that our thoughts will be largely rooted in imagery.

Take novelists, for example. While they typically exhibit a verbal cognitive style, many rely on visual descriptions to acquaint readers with their imagined world. Some writers even confess to being quite visual, using writing as a means of “painting pictures with words.”

Scientific and philosophical writing is also built on imagery. Unlike fiction, however, analytic thinkers rely less on detailed or vivid imagery and more on spatial concepts. Indeed, I suspect that much of what we call logic is founded on spatial observations and visual inferences of causation. If this is the case, the distinction between athletes and scientists is probably smaller than it’s often made out to be. Athletics and science both teach us about physics; science is merely a more abstract mode of study.

Verbal, Visual & Spatial Abilities

We’ve already seen how visual or spatial imagery may undergird and work hand-in-hand with language. But is it possible to excel at, or equally utilize, all three styles—verbal, visual and spatial?

Certain individuals (often of higher IQ) may excel or show competence with all three. They may, for instance, perform competently in language, art, and geometry courses. According to intelligence researchers, this may be due to higher levels of general intelligence, which allows a wide variety of skills to be acquired more quickly and effortlessly.

That said, Kozhevnikov’s research indicates that people rarely perform equally well on measures of object and spatial visualization, suggesting that there appears to be “a bottleneck that restricts the development of overall visualization resources.”

This makes sense in light of our earlier discussion about children possessing an innate preference for which sort of visual information is most interesting to them. Our early preferences seem to ensure that one mode of visualization is thoroughly developed and thus useful for certain types of tasks and purposes.

Do Personality Type & Cognitive Style Always Coincide?

Clearly there is a great deal of overlap between personality type, especially the T-F domain, and cognitive style. Earlier I suggested the early play and visual preferences are likely indicators of T-F preference. I cannot say, however, that there are never disparities between type and cognitive style, especially beyond the early stages of childhood.

From what I can tell, we inherit certain abilities from our parents that may be relatively independent of type. For instance, if both parents happen to be accomplished visual artists, it seems unlikely that any of their children would be without some measure of artistic ability, irrespective of personality type. So if the natural ability is already available, a child need only take interest in art to further develop as an object visualizer. Now it still seems that, on the whole, feelers are more apt to gravitate to art than thinkers, but if a thinker is imbued with natural artistic talent or is influenced in that direction by certain environmental factors, it’s certainly not out of the question.

The fact is that, given enough natural aptitude, an individual could feasibly excel at anything. And while I believe personality type is related to certain abilities, we also know that some talents seem to be inherited independently of type.

Moreover, when type and interests / abilities don’t neatly align (e.g., thinkers adopting stereotypical F interests), type confusion or dissonance is a likely result. For instance, an INFP scientist might find it easier, even if unwittingly, to self-identify as an INTP. While I generally don’t endorse mistyping, I can understand why individuals whose interests are atypical for their type might find comfort identifying with a different type.

Learn More in Our Books:

My True Type: Clarifying Your Personality Type, Preferences & Functions

The 16 Personality Types: Profiles, Theory & Type Development

Related Posts:

Learning Styles & Personality Type

Left vs. Right Brain: Paths to Meaning & Personality Type Differences

Thinking, Feeling, Intuition & Sensation: A Closer Look

References:

Alexander G, et al. “Sex Differences in Infants’ Visual Interest in Toys.” Arch Sex Behav. (2009) 38:427–433.

Kozhevnikov M, Blazhenkova O. “The New Object-Spatial-Verbal Cognitive Style Model: Theory and Measurement.” Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 23: 638–663 (2009)

Lamminmaki L, et al. “Testosterone measured in infancy predicts subsequent sex-typed behavior in boys and in girls.” Hormones and Behavior. Volume 61, Issue 4, April 2012, Pages 611-616.

Rehnman J, Herlitz A. “Women remember more faces than men do.” Acta Psychologica. 124 (2007) 344–355.

Sternberg R. Handbook of Intellectual Styles. Springer. 2011.