In 2009, I founded Personality Junkie® and began writing about personality typology. One of the reasons I titled the website as I did was I didn’t want to limit myself to writing about a single taxonomy. This still holds true today as I continue to explore, compare, and contrast the Myers-Briggs, Big Five, Enneagram and other relevant frameworks.

At the time I started this site, there was a lot of circulating and curated information about the Myers-Briggs types, as exemplified, for instance, by the MBTI Manual. Since then, however, research on the Big Five taxonomy has proliferated, contributing to its status as the leading academic and empirical model of our time. Considering the Big Five’s rise to ascendancy among academics, a few readers have asked us why we continue to emphasize the Myers-Briggs / MBTI® in our work.

Myers-Briggs / MBTI vs. The Big Five

In response to this question, one of the first things I usually point out is the Big Five doesn’t use personality “types.” Instead, it merely shows us where we fall, percentage wise, on each of its five categories compared to the general population. And while this does have the advantage of greater precision, the Big Five’s lack of personality types makes it harder to have community dialogues about one’s results. Personality types provide a user-friendly personality “snapshot” that is missing with the Big Five; they give us a sense of the forest instead of just trees. Sure, a few details may be lost along the way, but for type enthusiasts, it’s a worthwhile compromise.

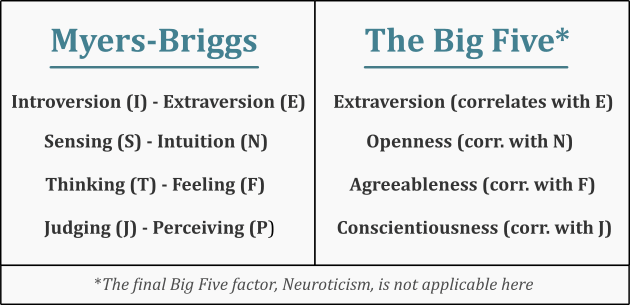

The second thing I like to underscore is that the Myers-Briggs preference pairs (i.e., E-I, S-N, T-F, J-P) share much conceptual overlap with four of the Big Five’s domains—extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness respectively—and research has consistently shown significant correlations between these two taxonomies. Even Big Five neuroticism to some extent correlates and overlaps with the Myers-Briggs:

Some have even proposed adding a fifth dichotomy to the Myers-Briggs types, turbulent (T) – assertive (A), which can better capture the characteristics associated with neuroticism.

Third, the Myers-Briggs includes a fascinating feature of types which is completely missing from the Big Five, namely, a hierarchy of functions. In his classic work, Psychological Types, Carl Jung outlined eight essential functions (e.g., Introverted Intuition). Myers-Briggs theorists later suggested that each personality type utilizes four of Jung’s functions, but prefers to use certain functions more than others (akin to how “right-handers” prefer their right hand). Having already written in depth about this issue elsewhere, I’ll make a very basic case for it here in a way that even Big Five devotees might appreciate.

Putting the introversion – extraversion attitudes aside for a moment, let’s simply look at Jung’s four basic functions: thinking (T), feeling (F), sensing (S) and intuition (N). We know that F corresponds to high agreeableness and N to high Big Five openness. But even feelers (i.e., agreeable people) can and arguably should use impersonal logic (i.e., be less agreeable) in certain situations, just as intuitives (i.e., open / imaginative folks) must also make good use of their senses (i.e., attend to concrete matters). The Myers-Briggs offers a great way of understanding and visualizing these opposing functions. As an example, let’s say a person receives the following Big Five results:

Extraversion: 70%

Openness: 75%

Agreeableness: 60%

Conscientiousness: 40%

These results indicate that Openness is strongest, which suggests a dominant preference for intuition. Thus, according to Myers-Briggs theory, sensing, as the dichotomous opposite of intuition, would constitute this individual’s weakest function. The results also suggest a preference for feeling (i.e., greater than 50% on agreeableness), making it the second preferred (i.e., auxiliary) function, and thinking the third / tertiary function. Hence, we are left with the following function hierarchy, which in this case, corresponds to the Myers-Briggs type ENFP:

Dominant: Intuition (N)

Auxiliary: Feeling (F)

Tertiary: Thinking (T)

Inferior: Sensing (S)

It’s important to realize that this arrangement is not a mere figment of Jungian imagination, but is both empirically and logically derived. Moreover, there are a number of ways this function hierarchy (a.k.a., “function stack”) might prove useful. First, it keys us into our preferred tool for understanding and navigating the world, that is, our dominant function. It can also help us better understand and empathize with individuals employing different functions.

Second, the function hierarchy offers us a framework for understanding our most salient strengths and weaknesses. Looking back to our earlier ENFP example, we’d expect to see strengths such as creativity, ingenuity, curiosity, and broad interests (i.e., stemming from intuition / openness) coupled with difficulties handling practical matters—appointments, money management, administrative details, etc. (i.e., stemming from inferior sensing). By grouping these things conceptually in terms of functions, it’s easier to see why we operate the way we do and, perhaps even more importantly, how we might grow and develop in our personality.

While it may be feasible to deduce some of this things from the Big Five as well, its non-dichotomous categories aren’t terribly helpful in this respect. Someone scoring high in openness, for instance, could easily fail to see much benefit in becoming less open. Approaching it in terms of the value of developing one’s sensing function, however, seems far more understandable and useful.

Concluding Remarks

At Personality Junkie, we are by no means opposed to the Big Five. In fact, we are regular consumers of Big Five research, which informs and enriches our work. However, as enumerated in this post, we believe there are good and valid reasons to continue using and developing the Myers-Briggs along side of it. Not only do the MBTI types offer a user-friendly personality snapshot, but their function hierarchies give us insight into each type’s strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for growth.

Learn more about type theory and the Myers-Briggs in Personality Junkie’s best-selling book, My True Type: Clarifying Your Personality Type, Preferences & Functions

Related Posts:

Personality in Politics: Myers-Briggs & the Big Five

Adele says

Excellent article, and something I’ve tried to explain to people for several years now, especially as a recent University student, but lack your gift for articulation.

I also believe that picking apart and trying to demote Myers-Briggs typology by academics in favor of the Big Five displays a bit of chronological snobbery, and perhaps frustration at the M-B foundation for governing the use of the instrument.

A.J. Drenth says

Thanks for your comment and feedback Adele. Glad you enjoyed the post!

Mikayla says

How does J-P / Conscientiousness play into the functional stack? I took the Big Five test and scored highest in Openness and next highest in Conscientiousness (followed closely by Agreeableness.) Does that J-P preference not play into the stack (…because the stack is only concerned with N-S, F-T)? When looking at the Big Five results, do we pay attention mostly to Openness and Agreeableness and ignore the others when trying to infer a stack?

A.J. Drenth says

Thanks Mikayla for your question. There are a couple ways to do the translation. In addition to high openness (N) and agreeableness (F), if you tested as more introverted, then based on N being your strongest/dominant, we could deduce that you’re an INFJ. Alternatively, you could simply translate the four relevant Big Five domains to Myers-Briggs preferences, which in this case, would give you the same result. There may, however, be occasions when these two methods don’t agree, as there isn’t a perfect correlation between the two taxonomies. If I recall correctly, the relationship between conscientiousness and judging is the weaker of the four. Perceiving (P) is also mildly correlated with openness, which can confuse matters a bit.