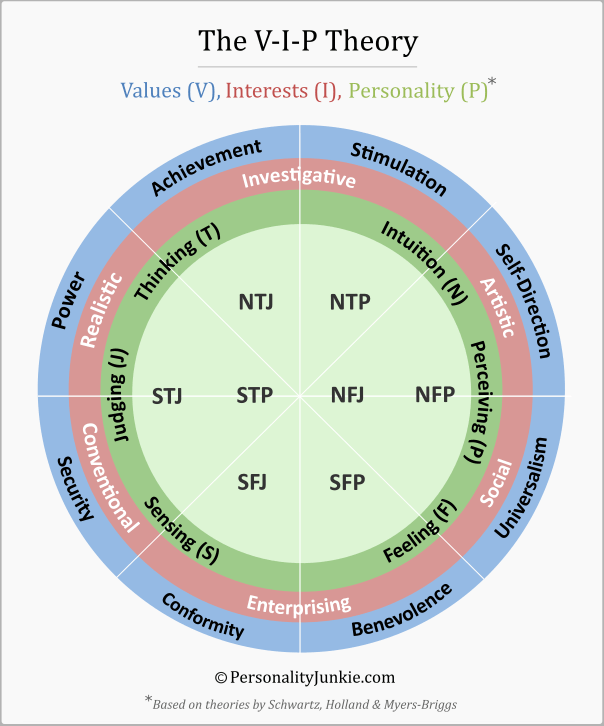

This is an addendum to a previous post in which I presented a synthesis of human values (V), interests (I) and personality (P) called the V-I-P theory. Since its publication in 2019, I’ve done additional theoretical work that I will integrate here.

Support from Eysenck’s Theory

I’d like to start with a smaller, but nonetheless relevant, point regarding how this theory overlaps with that of a renown voice in the history of personality studies—Hans Eysenck.

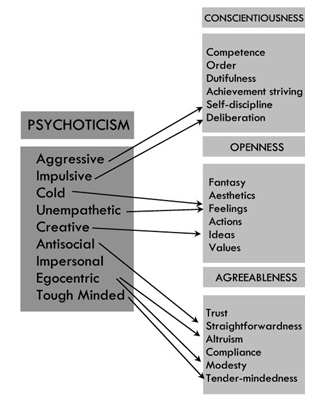

Eysenck believed there were three primary and independent factors of human personality: extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism. The Big Five, which is now the favored theory among academic personality researchers, preserved Eysenck’s extraversion and neuroticism, but decomposed psychoticism into: openness (+), agreeableness (-) and conscientiousness (-). Thus, in Myers-Briggs parlance, psychoticism would entail intuition (N), thinking (T) and perceiving (P). Psychoticism is also related to aggressiveness, which suggests that it involves some measure of extraversion (E) as well.

While I didn’t realize it at the time, the VIP theory is consistent with Eysenck’s work in that it includes and conceptually organizes traits which would have all been grouped under his psychoticism domain. In other words, the S-N, T-F, and J-P dichotomies are related in such a way that they can all be coherently represented together, as seen in the VIP diagram at the beginning of this post. And since they are all, roughly speaking, descendents of Eysenck’s psychoticism, I suspect he would have been largely in agreement.

The reason I originally omitted extraversion from the VIP theory was it didn’t fit well with the theories I was working to synthesize. This decision is further supported by Eysenck’s claim that extraversion is largely unrelated (a.k.a., “orthogonal”) to psychoticism (although aggression / assertiveness has since been linked with extraversion), and by extension, to S-N, T-F, and J-P. This shouldn’t be taken to mean that extraversion (or neuroticism for that matter) shouldn’t be included in a comprehensive model of personality, but its inclusion in the VIP theory would have likely added more noise than clarity.

The Brain Hemispheres

In his magnum opus, The Master and His Emissary, Oxford’s Iain McGilchrist masterfully details and analyzes decades of neuroscientific research on hemispheric differences. He demonstrates how the two hemispheres play distinct roles and thus offer surprisingly disparate versions of the world. One might even suggest that their clear anatomical separation is symbolic of their divided roles.

In this light, I’ve long felt that a sensible model of human personality must highlight left-right brain differences in some form or another. Failing to do so would not only mean ignoring an obvious physical clue (i.e., the divided brain), but also an abundance of empirical evidence. Fortunately, both the Big Five and Myers-Briggs, as well as the VIP theory, manage to capture important elements in this respect.

In her book, Personality Type: An Owner’s Manual, Lenore Thomson asserts that one’s status as a judger (J) or perceiver (P) is indicative of a preference for the left or right hemisphere respectively. This is reflected in the VIP theory, but not in precisely the way that Thomson is suggesting. I agree with Thomson that J types are more right-brained than their P counterparts, but only relatively.

Consulting our earlier VIP diagram, we find that judging is conveniently represented on the left side (corresponding to the left hemisphere) and perceiving on the right. However, you may have noticed that there is one group of J types (NFJs) to the right of center and one group of P types (STPs) to the left. This indicates that NFJs are apt to be more left-brained than NFPs, but aren’t necessarily left-brained overall.

To further illuminate this issue, let’s take a look at Big Five conscientiousness, which, as we saw earlier, corresponds to judging on the Myers-Briggs. Conscientiousness is in every respect a left-brained group of traits. While commonly overlooked in research literature, it is strikingly similar to the notion of executive control (also called executive functioning), which Wikipedia describes as:

Executive functions are a set of cognitive processes—attentional control, inhibitory control, working memory, cognitive flexibility, reasoning, problem solving, and planning—that are necessary for the cognitive control of behavior: selecting and successfully monitoring behaviors that facilitate the attainment of chosen goals.

Let’s now compare conscientiousness. In their paper “What Do Conscientious People Do?” Joshua Jackson and colleagues define conscientiousness as:

The propensity to follow socially prescribed norms for impulse control, to be goal-directed, planful, able to delay gratification, and to follow norms and rules.

We see many of the same central concepts—control, planning, and goals—in both definitions. I should point out, however, that executive control is not considered a personality trait per se, but is treated more like an ability, having been shown to correlate with measures like IQ and working memory.

We know that the left brain hemisphere is associated with detachment / abstraction—with constructing maps and representations of the world—which is a prerequisite for establishing goals, as well as formulating plans and regulating behavior in order to achieve them. Hence, its relationship to conscientiousness.

And insofar as conscientiousness tracks concrete behaviors such tidiness, cleanliness, or orderliness, it can be seen as oriented toward Myers-Briggs sensing (S) rather than intuition (N). This coheres with our VIP diagram, which features STJ types on one pole (i.e., left hemisphere) and NFPs on the other (i.e., right hemisphere).

Conceptually, we can see how intuition, feeling and perception—all of which are commonly cited features of feminine psychology—might work in concert with one another. Big Five openness in many respects embodies these characteristics. We can also envision how sensing (S), thinking (T), and conscientiousness (J) might work together in a symbiotic fashion.

In light of these trait clusters, we can better understand why Eysenck found it plausible to group them under the unifying umbrella of psychoticism. STJs and NFPs, for instance, can be described surprisingly well as “left-brained” and “right-brained” respectively. For other personality types, however, these broad descriptors may only be marginally useful and the need for additional dichotomies (i.e., S-N, T-F, J-P) becomes apparent.

In conclusion, the VIP theory remains a valid and useful approach for conceptualizing personality differences. I’m sure I will continue to revisit it over time as new studies and theories continue to emerge.