The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI®) is the most widely used personality instrument in the world. Over the last decade or so, however, it has become an increasingly popular target and strawman for typology skeptics eager to dismiss it is as unscientific. While there is ample research demonstrating that the MBTI® has at least a moderate level of scientific validity,1 I would like to explore this debate in a broader context, including chewing on questions such as these: Why has Jungian / Myers-Briggs typology become (and remained) so popular? What psychological needs does it satisfy? Is empirical validation the only thing that makes a theory valuable?

One could certainly argue, as skeptics are wont to do, that the hitherto popularity of the MBTI® has little to do with its scientific veracity. After all, beliefs in a flat earth or a geocentric universe were clearly wrong despite being embraced for centuries. With that said, one could also argue that theories about human beings are in an important sense different from those about the physical world. Indeed, we commonly see this people-things distinction in the sciences vs. humanities structuring of academic institutions. The study of human beings involves different types of data and methods, and may even require different truth criteria, than investigations of the natural world; at minimum, the phenomenon of consciousness seems a very different type of thing than physical processes. Therefore, when we consider that Jungian typology is a theory about human beings and belongs, at least in part, to the humanities, it is probably unfair to insist that it be scientific in the same manner as the physical sciences.2

According to thinkers like Kant and Jung, the human mind is not a blank slate, but is comprised of deep psychological structures that shape the way we experience and interpret reality. Not only do these structures influence our perceptions, but also our psychological needs and desires, including our desire to understand and find meaning in our lives. Indeed, I see Jung’s overarching concern as one of discerning the relationship between these psychological structures (e.g., archetypes, personality types) and human meaning / psychospiritual vitality, including their influence on art, philosophy, literature, and religion. Among other things, Jung’s work helps us understand why human beings are invariably drawn to things like myth, religion, and other forms of symbolism.

Differing Views of Truth

Although Jung liked to think of himself as a sort of clinician-scientist, he certainly wasn’t a scientist in the narrow sense typically employed by his critics. For such critics, the term “truth” is only properly applied to knowledge derived from a specific set of scientific methods. This is problematic for a number of reasons.

The first problem, which I touched on above, is that studying human beings, including consciousness in general, is apt to require a different tools and methods than those employed in the physical sciences. To conceive and approach human beings as a mere set of physical processes (i.e., reductionism) will undoubtedly result in a failure to understand the things we cherish most about human life, namely, its qualitative elements.

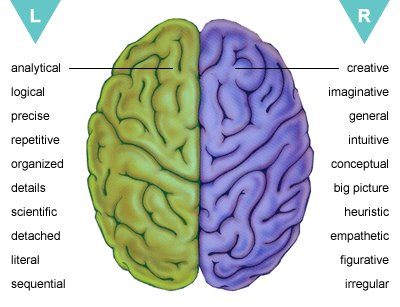

Second, when critics limit truth to only a narrow version of empirical science, they fail to give credence to our everyday experiences of truth and meaning, including that derived from the arts and humanities. Can we not find truth in art, fiction, music, or religion? When these things resonate with us deeply, we often use terms such as “true” or “real” to describe them. Thus, there are at least two ways we determine truth: through science / intellect and through experience. These dual modes of knowing are nicely illustrated in Seymour Epstein’s Cognitive-Experiential Self-Theory (CEST), as well as in the vast body of research enumerating left vs. right brain differences.

Accordingly, we might ask ourselves whether it is appropriate to restrict our view of truth to only one half of the brain (i.e., the “analytical” left hemisphere) or whether it is better to allow both hemispheres to weigh in on the matter. If we opt for the latter, the sphere of truth must extend beyond science and incorporate, among other things, insight and wisdom from the humanities. Of course, this is bound to complicate the means by which we define and evaluate truth. This is why some prefer to limit truth to the realm of left-brained science, which provides clearer boundaries and criteria for debating the merits of various truth claims.

Clearly, the degree to which we consider something true will depend on the way in which we assess and define truth, including our assumptions and preferred epistemology. If feelings (F) or intuitions (N) are allowed to participate at our truth roundtable, we may well arrive at a different conclusion than if only thoughts (T) and sensations (S) are granted a say. Moreover, one could argue that each of these psychological approaches will be more (or less) useful depending on the situation. Feelings, for instance, are apt to be of less value when repairing a flat tire versus navigating human relationships. Thus, determining which tools and methods are most conducive to a particular problem is of obvious value.

With this in mind, let us now consider the nature of the problem or set of needs that Jungian typology aims to address. At minimum, it seeks to:

- Identify and classify individual differences (and similarities) in human personality and behavior

- Inform our self-understanding and self-development

- Help us better understand, empathize, and abide with others

Interestingly, one could propose a rather similar list of objectives for psychology in general, as well as for religion. This should come as little surprise to those familiar with Jung’s work, which reveals significant overlaps between psychology / typology and religion; both offer explanatory theories of the human condition, as well as potential ways of improving it. Considering these similarities, the degree to which we ascribe truth and value to typology vis-à-vis competing belief systems will hinge on its effectiveness in satisfying our expectations. If our chief desire is a scientifically-derived (in the narrow sense) account of human psychology, we may be left wanting. If, however, our expectations are more holistic, involving an admixture of truth, meaning, and elegance, we are more apt to find it compelling. In my view, the widespread interest in Jungian / Myers-Briggs typology speaks to its holistic appeal.

Beyond Scientific: The Importance of Elegance

Relatedly, one could argue that the beauty or elegance of a theory plays an important role in its appeal or palatability. As Chad Perrin explains in his article, “Elegance,” beauty / elegance entails a balance of simplicity, complexity, effectiveness, and appropriateness:

Elegance is not about aesthetics. Rather, aesthetics is about elegance. Ostentation lacks aesthetic appeal, and is inelegant (read: “tacky”), because it’s gratuitous. Simplicity is often not elegant either: if something is too simple, it is nonfunctional, and fails to achieve its aim. What makes something beautiful is not strictly simplicity, symmetry, complexity, or any other such characteristic. Instead, what makes something beautiful is that its characteristics are all appropriate to its purpose. Complexity can be exceedingly beautiful, as long as it’s not gratuitous complexity, which is just chaos and confusion. Likewise, simplicity can be exceedingly beautiful, but if you make something gratuitously simple, you get dullness rather than beauty.

I love Perrin’s notion that something is beautiful when “its characteristics are all appropriate to its purpose.” This is why, when evaluating a theory like Jungian typology, we are behooved to first consider its purpose—what it aims to accomplish and what we expect from it.

Of course, we can’t really measure elegance in the same way we can measure something like the speed of light. This is because elegance is in large part assessed holistically or qualitatively rather than quantitatively; in many respects, we “know it when we see it.” It is through this sort of qualitative assessment that we have come to recognize, among other things, great works of art and literature. Granted, there is bound to be some measure of disagreement regarding what constitutes elegance. After all, if the individual is designated as the primary arbiter of elegance, such disputes are all but inevitable. And while such disagreements are rarely fully resolved, they can be partially overcome through dialogue and democratic processes.

The Myers-Briggs / MBTI vs. The Big Five

But what about popular academic models of personality? How does the Myers-Briggs stack up, for instance, against the Big Five?

First, it is worth noting that these two frameworks are in some ways quite similar and their major constructs have been shown to consistently correlate with each other. Second, the Big Five is significantly younger than the Myers-Briggs, so it remains to be seen whether it will surpass it in popularity among the general public.

With that said, my sense is that although the Big Five may have more empirical backing than the Myers-Briggs, it is not as theoretically elegant. And because many (most?) typology enthusiasts are drawn to elegance, the Myers-Briggs will likely retain its favor among the general public. If this proves to be the case, it will continue to be a favorite target of typology critics who fail to understand its aim, purpose, and value.

Personality typing is not merely an analytic process, but offers an elegant and inspiring account of who we are, as well as paths to growth and fulfillment. There is a satisfying sense of identity and unity that comes from knowing one’s type (e.g., INTP) that is missing from the Big Five. The Myers-Briggs types are also more life-like, familiar, and recognizable, described in everyday terms such as thinking, feeling, sensation, and intuition.

Learn More in Our Books:

The 16 Personality Types: Profiles, Theory & Type Development

My True Type: Clarifying Your Personality Type, Preferences & Functions

Related Posts

Myers-Briggs / MBTI in the Age of the Big Five

Openness, Myers-Briggs Intuition, the Big Five, & IQ Correlations

Left vs. Right Brain: Paths to Meaning & Personality Type Differences

Notes

- See The MBTI Manual, a valuable compendium of MBTI research.

- Here, I am essentially siding with the antipositivists / interpretivists who suggest that “the social realm is not subject to the same methods of investigation as the natural world. The social realm requires a different epistemology in which academics do not use the scientific method of the natural sciences.”

- Just to be clear, I’m not suggesting that we eschew rationality or the findings of science, both of which can inform our view of reality and benefit our lives. Moreover, embracing beliefs that patently contradict scientific consensus (e.g., denying climate change) may ultimately imperil our collective health. But in order to live well as human beings, we must find ways of balancing and integrating both the rational / scientific and non-rational elements of life.

Architect says

I’ve followed the ‘MBTI isn’t science’ articles too. The mistake they’re making is not uncommon, which is not sufficiently understanding the nature of what constitutes science, and particularly a scientific theory. The main requirement of a theory is that is it falsifiable, which means that an experiment could be conducted which gives different results than the theory predicts. Taking Newtons Law of Gravity for as an example, it predicts how objects fall very precisely. All you need to prove it wrong is to measure a time when it doesn’t fall according to Newton. Simple, right?

Wrong. It’s quite easy to prove Newton wrong – near a black hole or the sun for example. And Newton says nothing about time – for that you need Einsteins General Relativity, which is a gravity theory which supplants Newton. Where does that leave us? Not that Newton was wrong, but he was incomplete. Einstein came along and made a better theory, which is more complete. However, GR actually isn’t really complete (we think) – because it doesn’t work well with Quantum Mechanics. So there must be some greater theory which accounts for Newton, Einstein _and_ quantum mechanics. And so forth … But see? There is a descriptive aspect to theory as well as a prescriptive. The best theories have both broad coverage, and they lead us to knowedge we didn’t have before (e.g. nobody knew a thing like a black hole existed, but Einstein showed us the way before we discovered them astronomically)

With MBTI, it would predict that a type will want to spend its energies in dominant and auxiliary related activities. That is a statistically verifiable and falsifiable test. Further, like any other good theory, MBTI makes predictions that we wouldn’t make a priori. No, MBTI is just fine as a scientific theory, and for the life of me I don’t understand why mainstream psychology holds a grudge against it.

MC says

Yes, I think the main post touched on some nice aspects of the value of humanistic analysis (probably more applicable to things like the Enneagram), but I think you’re closer to the mark of where the “it’s not scientific” crowd are coming from — a mischaracterization of the scientific process itself. I’ve also found that such critics wave “peer review” around like a flag denoting a binary valid/invalid status, but seem to misunderstand that peer review is itself a process, a give and take.

FWIW, I think a lot of the bias comes from the fact that Myers and Briggs were not part of the “mainstream” psychology lineage. Academia has an elitist bias and I think there has been resistance to the idea that two “outsiders” (women especially!) could contribute a pragmatic, elegant theory — hence the development of Big 5, which captures much the same information as MBTI yet was developed “in-house.”

eselpee says

The Big Five is so general that it cannot be wrong. Of course it is also unsatisfying and does not support self-understanding.

Neuroscience recognizes the irony in using our brains to understand our brains.

Additionally, neuroscience has not developed a consensus definition of “mind” or “thinking” or “consciousness”.

We are still a long way off from understanding human personality traits

I could say so much more about the hypocrisy of the APA

Michele Italy says

This site led me to approach Jung’s original works, and tge first two of them led me to the proposal of reading the entire corpus.

Jung… and the Oriental knowledge (real zen, real yoga) he talks on, are what I needed.

If not, not at all!, a twin in intellugence, I found a twin in feeling and intuition in him.

thanks to his writing I can now know Why I “see” things others even more intelligent do not (it’s through Ne and Fi), and why art gives us the shivers even if we don’t rationally understand it much (the primordial archetypal region of the mind is common… for the author and the reader/listener/viewer… so they vibrate together)

And much much else.

Thanks for this too, Dr. Drenth

Roy says

Well this whole debate about what constitutes truth in the mind of the skeptic is exactly the problem with their perception of truth as a whole. Their very strong belief in scientism or scientiffic materialism constitutes an almost religious frenzy for many of them. Such a strong belief tends to thwart any attempts by them to comprehend the role of consciousness in the sciences, and the implications of the newer, more accurate scientific theories of relativity and quantum mechanics. Their so-called objective truth belongs to the naive material realism of a previous era, and this defeats their capacity to transition to more accurate ways of understanding.

Of course, we are organisms, not the conjectured machines in the philosophy of scientific materialism. Naturally, our brains cannot and should not be confused with computers as the naive realist are won’t to conjecture. Again, we are dealing with a form of immature or incomplete reasoning when it comes to the pseudoskeptics as they are coming to be known. I think it may take a awhile before these older, debased forms of thinking get sorted out, and they accept the newer paradigms of relativity and quantum theory. Then they will discard their obsolete mechanistic ideas about the mind and brain which have failed to produce any evidence.

Sarah says

I don’t find this argument convincing. One of the major issues raised against MBTI is its lack of repeatability, which you have not addressed. There are also issues where descriptions of the types differ depending on whether someone is using opposing dichotomies or Jungian function theory. The mere facts that so many people misidentify their type, and it’s a “best fit” rather than universally accurate, demonstrates flaws in the theory. There is an inherent assumption that the functions exist as stated, without further evidence that this is case, and an assumption that people use them in a particular way.

The reason I value MBTI is that it’s a thought framework, a structure within which to have discussions. It is useful, undoubtedly. I have found it far easier to work with a colleague since pinning her down as Si-dominant and approaching her with that assumption. The ability to put people in ‘boxes’ and approach them accordingly provides good utility. That doesn’t mean that the theory is correct.

(As an interesting aside, my probably-ENTJ husband immensely dislikes putting people in boxes and believes it impairs the ability to approach them as individuals and optimise your relationship with each person, but a ESTJ former colleague found it such a useful tool that she got certified as a MBTI tester.)

michael kiyoshi salvatore says

I agree with much of what you say here — there’s an evident bias within the ‘hard’ sciences against anything that can’t be rendered statistically, materially, and causally

There’s also much to be said for ‘everyday experiences of truth and meaning’ as found in the arts and humanities

One thing I haven’t seen jungian type confront is its inherently metaphysical nature and closed structure, which many potential antipositivist allies reject on principle. This is one thing held in the Big Five’s favor; it’s trait-based, emphasizing spectrums of possibility, while type has much baggage as essentialist left to unpack. I think it’s especially hurt by the four-letter code in this regard, as the J-P E-I T-F S-N axes seem pretty fluid, while the cognitive processes can only be understood as deep-rooted

I’d also add a lot of dissatisfaction I find with the Big Five comes from its unipolar bias towards a defined set of Better Traits — extroverted, conscientious, etc.