At the heart of the Myers-Briggs is the notion that we all have psychological preferences. Some of us rely more on Intuition, others on Sensing, and so forth. It would be foolish, however, for us to believe we can survive, much less thrive, using only one mode of operating. This would be akin to a right-handed person believing they’d do just as well without their left hand.

Carl Jung, the founding father of psychological types, understood this as clearly as anyone. While he conceived the psyche in terms of opposing functions (e.g., S-N, T-F), he took care to place them all on a level playing field, seeing no function as inherently better or more valuable than another. And while it’s true that we all have a dominant function, we need to incorporate all the functions to experience the life to the fullest. Hence, from a Jungian perspective, personal growth involves continuously developing and integrating different functions.

Nevertheless, there are times when we can’t help but jump on a bandwagon, elevating one aspect of our psychology, or perhaps a promising self-help technique, over and against all others. At such times, we may feel we’ve found the Holy Grail to happiness, thus obviating the need for anything else. It’s rarely long, however, before life reminds us of its infinite complexity and swiftly dispenses with our simplistic conceptions.

As an avid consumer of psychological research, I tend to notice what’s trending among researchers and laypersons. Currently, it seems one can’t go anywhere without seeing a new headline about the benefits of mindfulness or meditation. While I’ve personally benefitted from meditation, I don’t see it as a panacea. With every proposed therapeutic, I think we should consider its potential downsides, explore the value of alternative approaches , and try to keep the “big picture” of human psychology in mind. In so doing, we give credence to the complex and multidimensional nature of the psyche, as well as life in general.

The “Big Picture”: Stability & Novelty

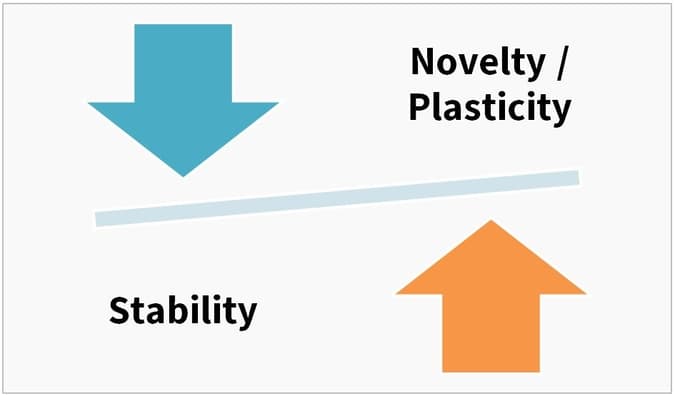

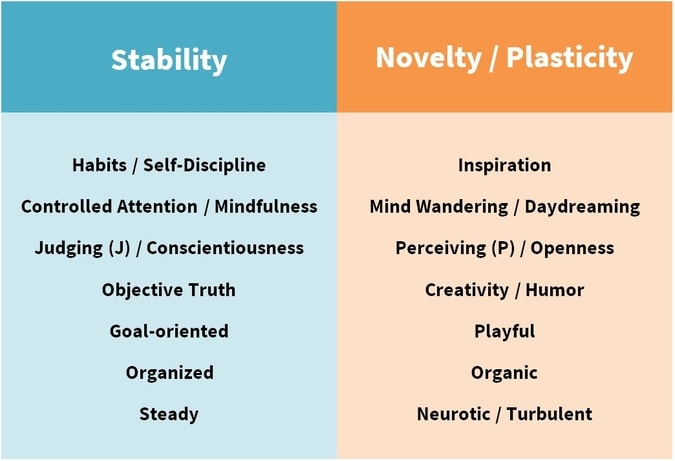

So what do I mean by the big picture of human psychology? One example is my synthesis of several well-established theories of values (V), interests (I), and personality (P), which I dubbed the “VIP Theory.” Among other things, the theory posits an overarching dichotomy of human personality—one of stability versus novelty / plasticity.

Not incidentally, this dichotomy is reflected anatomically in the left and right brain hemispheres respectively. Notwithstanding the fact that some individuals are more stability oriented (e.g., ISTJs) and others more change or novelty oriented (e.g., ENFPs), both of these tendencies play a prominent role in every human life.

Moreover, many of the central issues of human psychology can be roughly categorized as either stability or novelty / plasticity oriented. Here are some examples:

Once we acknowledge that stability and novelty are, for all intents and purposes, equally important and necessary, it becomes much harder to consider any singular attribute or growth strategy the “end all, be all.” We seem most susceptible to jumping on bandwagons when we’ve swung too far in the direction of either stability or instability. When we feel like our lives have become too mundane or predictable, for instance, we might start idealizing or dreaming about something that will add variety, interest, or excitement. Likewise, when we’re feeling aimless or overwhelmed, we turn to the stability side of the spectrum to impart a sense of calm and order to life. Individuals with a more neurotic or turbulent disposition may feel they are constantly swinging between these two extremes. They may feel bored and depressed one day (i.e., stable to the point of feeling disinterested) and anxiety ridden the next. In the first case, they feel under-stimulated, in the second, over-stimulated.

At this point, you may be thinking to yourself: What about a third option? Isn’t there a middle way, a “third-hand” solution, that marries these two poles of human psychology?

Flow: A Unified Experience

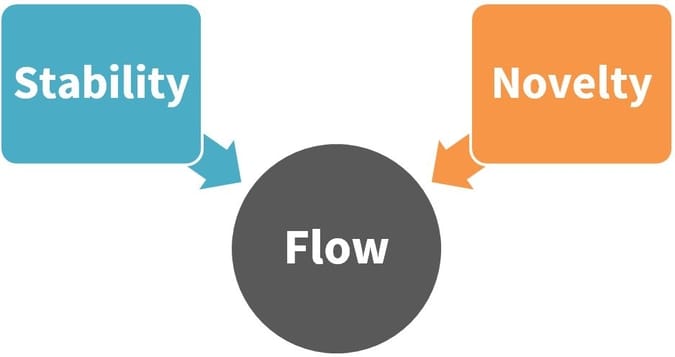

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has contended that flow experiences represent the “optimal” state of human attention and engagement. I tend to agree. Flow seems as good a representative as any of the “sweet spot” between stability and novelty.

Flow occurs when a task provides us with just the right amount of challenge and stimulation—shooting the middle between boredom (lack of challenge / interest) and undue stress (too demanding). When immersed in a flow state, we tend to “lose ourselves” in what we’re doing, enjoying a sense of unity and purposiveness.

According to Csikszentmihalyi, flow is a deeply pleasurable and rewarding state of being, perhaps more than any other. If this is the case, we might do well to start talking less about happiness and more about flow. The challenge, however (which is far trickier than it initially sounds) is how to consistently procure flow states.

In a sense, we’re trying to lay the grounds for flow by seeking the “right” career or romantic partner. We instinctively realize that flow is more likely when engaging with certain types of work or people.

But tweaking these sorts of external variables can only take us so far. We also need to self-calibrate—addressing our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors—to prepare the way for flow.

So how is this accomplished? How can we become skilled technicians of our own psychology?

Unfortunately, there is no simple or singular answer here. At times, flow seems to have a mind of its own, emerging spontaneously without conscious effort or forethought. But if we want to experience flow more regularly, we need to understand how the human mind in general, as well as our minds in particular, tend to operate. This means revisiting some of the stability-novelty variables we listed earlier.

The left side of the brain contains tools for increasing stability and consistency (e.g., developing habits), whereas the right offers paths to novelty and meaning. We can draw on either side in accordance with the demands of our current psychological state and external circumstances, thus improving our odds of finding flow. The more we familiarize ourselves with how these various tools affect our overall experience, the better our chances of success.

While some tools may seem more impactful than others, this is typically true only under certain conditions. Windshield wipers are extremely useful while it’s raining, but not so much on sunny days. We should thus exercise caution in getting attached to any particular tool. Single-mindedness invariably begets imbalance, creating a situation where our favorite tool can end up working against us rather than for us. To circumvent this problem, Jung argued for the importance of the “transcendent” function, a sort of wise manager that can discern which psychological tool is most appropriate for a given circumstance. Wisdom is thus our greatest asset for finding flow with any regularity.

Learn more about integrating novelty and stability through the lens of personality type in our online course, Finding Your Path as an INFP, INTP, ENFP or ENTP:

Read More:

The “Flow” Experience: The Art & Beauty of “Losing Yourself”

Left vs. Right Brain: Paths to Meaning & Personality Type Differences

Values (V), Interests (I) & Personality (P) Type: A Unified Theory

John C. says

Great article, concise and right at the point. As an INTP, all points makes sense and connecting the dots in a big picture. ‘Wisdom’ will be our guide to find that ‘flow’ and balance between stability and novelty. 5-min-analysis is my habit everyday I use to achieve that wisdom to see which functions to utilize in certain situations. Thank you for the article.

A.J. Drenth says

Thanks so much John for your comment. Great to hear you enjoyed and resonated with the post.

Andrew says

Thanks, this is great post. I like how you land on wisdom. It feels our culture is drowning in knowledge but starving for wisdom.

A.J. Drenth says

You’re welcome Andrew. I appreciated your notion of “drowning in knowledge but starving for wisdom.”