If I’m being honest, I have a love-hate relationship with the Enneagram. My left brain—the deliberate and analytic side—struggles with its unscientific basis, which can make aspects of Enneagram theory seem rather arbitrary. At the same time, after spending several days knee deep in Big Five research, revisiting the Enneagram feels like a breath of fresh air, reminding me of the value and meaningfulness of “whole types.”

Historically, I’ve focused largely on the Myers-Briggs because it sort of splits the difference between the Enneagram and the Big Five, engaging both the holistic and analytic sides of the brain. Does this mean the Myers-Briggs is the perfect model? Of course not. In fact, if I were to rebuild it from the ground up, I’d certainly make a number of tweaks and revamps. But that discussion will have to wait for another day.

In this post, I want to spend some time picking on the Enneagram (in a gentlemanly sort of way of course). Before donning my critic hat, however, I want to say a bit more about why I think the Enneagram is valuable and, notwithstanding its scientific shortcomings, may be here to stay.

What I Love about the Enneagram

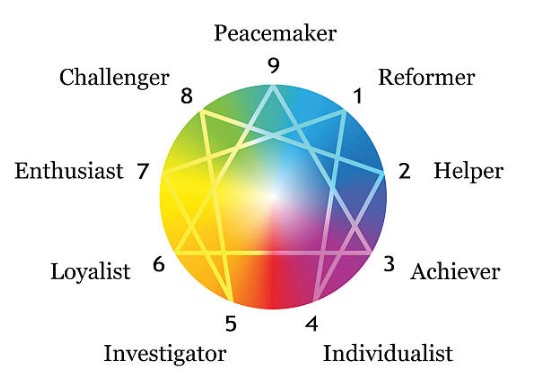

As I hinted at above, I love the holistic understanding and meaningfulness conferred by the Enneagram types. Hearing that someone identifies as an “Artist / Individualist” (Enneagram type 4) or an “Investigator” (Enneagram type 5), for instance, conveys a wealth of meaningful information. The mental image evoked by these descriptors is so complete that we instantly grasp their meaning, even if we’re Enneagram newcomers.

Moreover, the Enneagram’s independence from science may prove advantageous with respect to allowing greater freedom in our choice of type. One might even opt to grant less attention to who she already is, focusing instead on the personality type she aspires to embody. Indeed, using type in the service of self-creation rather than merely self-discovery can be deeply empowering. Self-creation is a process of personal transformation driven by one’s vision of a desired future self. And the Enneagram types can function as potent images for self-creation and self-development.

In striving to keep one at least one foot planted in scientific territory, the Myers-Briggs can’t offer the same degree of freedom in choosing one’s type. While some have opted to slap Enneagram style nicknames on the Myers-Briggs types, this becomes problematic if someone tests as an INTP, for instance, but doesn’t resonate with the assigned moniker (e.g., “Architect”). What if she tests as an INTP but resonates with the INTJ’s “Mastermind” nickname instead? Should she betray her test results and identify as an INTJ, or should she simply disregard the nicknames altogether? (Note: the official MBTI does not assign nicknames to the 16 types). Situations like this highlight the fact that even Myers-Briggs devotees cannot escape the scientific – holistic tension I described earlier. This is because we all seek a scientific level of certainty and validation for who we are (left brain), but also want our type to inspire us and provide a vision for self-transformation (right brain).

What I’d Change about the Enneagram

For us hardcore personality junkies, finding our type is never enough; we always want to learn more. We want to uncover all the details about ourselves and enjoy endless “eureka moments.” However, such forays into the nitty-gritty of our type, and especially into its logical structuring, move us away from the holistic and emotional right hemisphere and toward the analytical left brain. Thus, what starts with the joy of finding our type gives way to a more detached and analytical mindset.

Assuming that Enneagram theorists also have left hemispheres, it’s no surprise that they too have imposed theoretical rules and constraints on the types. Alas, the Enneagram couldn’t persist as merely a beautiful collection of nine types, but was instead treated like an unfinished painting that, despite the risk of looking gaudy and overworked, continued to amass new speculative theories and extrapolations over time.

I know we must the give the left brain its due. We can’t just stop with the “I found myself” feeling of discovering our type and expect the left hemisphere to be satisfied. Moreover, theorists can’t help but theorize and try to make sense of things. I get it. But there are times when extensive theorizing, especially without the oversight of the scientific method, can create more chaos than clarity, detracting from the initial elegance of the framework.

To be clear, I’m by no means opposed to fleshing out the details of the Enneagram types. For instance, I love how Don Riso and Russ Hudson in their book, Personality Types, provide thorough descriptions for each of the nine types, including their different levels of health and development. Great stuff!

My main point of concern and critique has to do with the proposed theoretical rules and constraints pertaining to the Enneagram “wings.” As students of the Enneagram will already know, Enneagram theory posits that each type is limited to two wing options, namely, its two neighboring types on the diagram:

Wings provide more specifics about an individual’s personality and motivations, playing a similar role to the auxiliary function in Myers-Briggs theory. For example, an Enneagram type 5 can select either a 4 or a 6 wing. This implies that the Five cannot or doesn’t readily combine with any of the other types. However, if you’ve ever taken an Enneagram test and observed how your scores are distributed, you may have seen how problematic this can be. For instance, while most INTJs test as Fives, others may test as Ones, Threes, etc. Moreover, many INTJs will have Five as their main type and One or Three as their second preferred type. Unfortunately, Enneagram theory doesn’t allow these poor INTJs to identify as a 5 with a 3 wing (i.e., 5w3), which might be called the “Investigator – Achiever,” since the 4 and 6 wings are the only available options. We see a similar problem with INFJs. Many INFJs will test as Fours, but also as Nines, Ones, or Twos. And because 4w9, 4w2, or 4w1 aren’t considered legitimate subtypes, INFJs are often forced to adopt a less suitable wing.

I realize that opening the floodgates and allowing individuals to select any type as a wing may disrupt other aspects of Enneagram theory. But I think the benefits could well outweigh the risks. Imagine an ENFP Seven, previously limited to calling herself an “Enthusiast – Loyalist” (7w6) or “Enthusiast – Challenger” (7w8), suddenly having options like “Enthusiast – Individualist” (7w4) and “Enthusiast – Reformer” (7w1) to choose from. Not only would this allow greater accuracy in self-description, but also more options for self-creation. No longer would we be limited to only two wing options, but could freely choose whichever types and wings best reflect and resonate with us.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that all personality models should divest themselves of theoretical rules and constraints. In my view, neither the Myers-Briggs nor the Big Five should adopt this as its motto. What I am saying is that the Enneagram, as a non-scientific model, should resist the temptation to overlay its types with elaborate, speculative theories which all but ensures its dismissal as pseudoscientific. It should instead embrace its strength as an elegant menu of types and roles which can serve as a source of meaning, identity, and inspiration.

Learn more about personality type and theory in our four books and online course, Finding Your Path as an INFP, INTP, ENFP or ENTP.

Read More:

Myers-Briggs & Enneagram Correlations

Enneagram vs. Myers-Briggs: Key Differences

Enneagram Profiles: Type 1 | Type 3 | Type 4 | Type 5 | Type 6 | Type 7 | Type 9