I’ve been kicking myself recently. Over the last several years, I’ve touched on the concept of “flow” in no fewer than 10 articles as well as in my book, The 16 Personality Types. But for some reason, I never got around to posting about it. So lest I suffer any further regret and self-reproach, I’m dedicating this post to this fascinating and important topic.

Let me start by giving credit where it’s due. The late Hungarian psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, coined and popularized the flow concept, which is also described in terms of “flow states” or “flow experiences.” In addition to his formal research, he published a number of popular books about flow, which he considered the “optimal human experience.” Clearly, flow was near and dear to his heart, as it is to mine.

The Flow State: Psychological Features & Benefits

Flow is largely synonymous with what athletes call “being in the zone.” According to Csikszentmihalyi, there are six key features of flow:

- Focused concentration on a given task or activity

- Merging of action and awareness

- A loss of reflective self-consciousness

- A sense of personal control and competence

- Experiencing the activity as intrinsically rewarding

- An altered perception of time (i.e., time “flies” by)

In short, flow involves “losing ourselves” in activities where we feel capable, competent, and meaningfully engaged.

Importantly, Csikszentmihalyi associated flow with active rather than passive forms of engagement. While it’s certainly possible (and not uncommon) to lose ourselves in a television program, for instance, he saw these sorts of passive activities as ultimately less rewarding than those that are more challenging and offer opportunities for personal growth and accomplishment.

Understanding flow (and how to achieve it) is important because it’s a deeply rewarding experience, both during and following the activity. Not only are we happier and less neurotic when immersed in flow, but we typically feel good about ourselves and what we’ve accomplished afterward.

Flow has also been linked to superior performance in teaching, learning, athletics, scientific and creative fields, etc. Athletes performing at exceedingly high levels—such as basketball players who “can’t miss”—are typically assumed to be in a flow state.

Considering its subjective and objective benefits, it’s little surprise that Csikszentmihalyi deemed flow the optimal type of human experience.

Cultivating Flow: Helps & Hindrances

Despite its myriad rewards, most of us don’t experience flow as often as we’d like. It’s therefore critical to identify the precursors to flow and find ways of leveraging them for our benefit.

One key factor, according to Csikszentmihalyi, involves finding the appropriate level of challenge and stimulation. If the demands of an activity exceed our level of skill or ability, we’re apt to feel anxious, frustrated, or overwhelmed. Activities perceived as “too easy” may also hinder flow, contributing to boredom and the sense that time is “dragging.”

In emphasizing the congruence between skill and challenge, Csikszentmihalyi implicitly acknowledged the importance of recognizing our personal strengths and abilities. There are numerous ways of doing so, including identifying and understanding our personality type. Learning about our type’s dominant function, in particular, can tell us a lot about where we might naturally excel and, in turn, discover greater access to flow states.

Surprisingly, Csikszentmihalyi wrote comparatively little about the role of values and interests in cultivating flow. However, experience suggests that if our values and interests aren’t sufficiently engaged, we’re apt to feel bored and unmotivated. So finding flow not only requires knowing what we’re good at, but also what we enjoy and are passionate about.

When it comes to impediments to flow, distractions are at the top of the list. As we’ve seen, flow entails a merging of “action and awareness.” So by scattering our attention, distractions prevent this merger from occurring.

In some cases, distractions are circumstantial and can be reduced by modifying or changing the task environment. In other cases, the source of distractedness is more psychological, marked by an inability to stay focused on a task or goal. This may stem from diminished executive control, which helps us maintain focus and filter out irrelevant information or stimuli. Fortunately for those who struggle with distractibility, our level of executive control isn’t fixed, but like most skills, is amenable to improvement.

Anxiety, depression, and other negative emotions may also discourage flow. As mentioned earlier, flow occurs within an optimal range of stimulation—somewhere between too much and not enough. Individuals with high levels of anxiety may thus struggle to find flow, as can those who are bored, depressed, or otherwise disengaged.

Left & Right-Brain Contributors to Flow

As discussed in my post, The Big Picture of Human Psychology, cultivating the conditions for flow depends on contributions from both sides of the brain.

The right hemisphere furnishes much of the energy, curiosity, and meaning we need to stay engaged and motivated. Creative types, in particular, place a lot of stock in the experience of inspiration, which impels them to put pen to paper, brush to canvas. Without this surge of energy and motivation, their work can feel lifeless, perfunctory, and frankly “uninspired,” thus hampering their ability to find flow. This ties into our earlier discussion of values as precursors to flow. Namely, inspiration might be seen as an emergent or spontaneous value, one which creatives are eager to grab hold of, lest it vanish as quickly as it appeared. Values are foundational in non-creative fields as well, furnishing the emotional energy and motivation to keep us moving forward in our life and work.

On its face, flow might seem like a predominantly “right-brained” phenomenon, something that spontaneously or mysteriously overtakes us. Not unlike the experience of falling asleep, there’s a sense that we fall into flow. In this light, one might conclude that flow has “a mind of its own” and that we have little control over its comings and goings. But this would be akin to believing that there’s nothing we can do we can do to get a better night’s sleep. Sure, we might not be able to control the exact moment we fall asleep or enter a flow state, but there are things we can do beforehand to increase our chances of success. This requires drawing on some key tools of the left hemisphere.

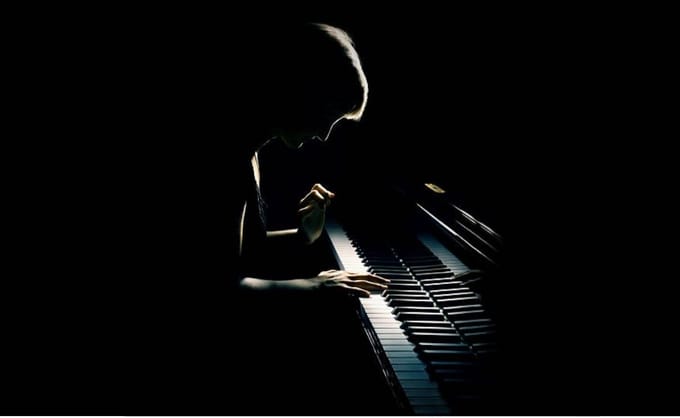

The “left brain” contains tools for enhancing stability, reliability, and consistency, such as developing effective habits, which lay the groundwork for the emergence of flow. Finding flow as a musician, for instance, doesn’t happen overnight. Countless hours of practice and rehearsal are needed before our musical instrument feels like “part of us” and flow states start to emerge.

Flow conforms to the laws of momentum. The more frequently we experience flow in a certain context, the greater the speed and likelihood of its future recurrence. If flow is essentially a brain state, building momentum through effective habits paves and substantiates flow-pertinent pathways.

That said, even flow “maestros” must overcome some upfront resistance. Doubts, distractions, worries, lack of clarity, etc.—all can precede and preclude the emergence of flow. You’re probably familiar with the notion of “the calm before the storm.” With flow, however, it’s usually the opposite. Namely, we must be willing to weather psychological storms before a calm and steady flow state finally sets in. At times, these “storms” can be consciously quieted through various techniques and strategies; but not always. Just as often, flow comes as a result of patience, persistence, and a sense of optimism.

For writers like me, this means putting myself in front of my laptop day after day, trusting that meaningful clusters of words and ideas will start forming in mind. It can also mean writing God-awful sentences as a means of jumpstarting the flow of ideas. I’m still surprised by how flow states can break through even on “bad days” —like the sun piercing a row of dark clouds—if I can manage to remain patient and optimistic.

This highlights yet another of flow’s many benefits. By corralling the mind into a state of synchrony, it can effectively U-turn our emotions, rescuing us (at least temporarily) from the perils of neurotic or divided thinking.

Closing Remarks

Religious teachers and students of meditation often cite the experience of unity or “union with God” as the ultimate spiritual achievement. Flow is essentially the same thing, with the main difference being that it emerges from activities other than focused prayer or meditation. Either way, there’s a loss of self-consciousness which we experience as deeply pleasurable, even spiritual.

I personally see flow as a sort of oasis from the struggles and vicissitudes of life. Even when things aren’t going my way, I’m reassured by the fact that, for a few hours a day, flow can help me forget about myself and my concerns.

To be sure, the context and antecedents of flow can look quite different from one person to the next. While my approach as an INTP is predominantly Introverted, for Extraverted or Feeling types, flow often emerges from engaging with or caring for others. Hence, it’s largely a matter of identifying what sort of activities and situations we readily get absorbed in and lose our self-consciousness. Ironically, we seek to understand ourselves with the ultimate aim of losing ourselves which, in turn, helps us feel better about ourselves. Ah, the wonders of human existence!

To better understand yourself, your personality, and how to cultivate a life of purpose and flow, be sure to check out our online course, Finding Your Path as an INFP, INTP, ENFP or ENTP. It’s a doorway to transforming your inspiration into meaningful and effective action:

Read More:

Left vs. Right Brain: Paths to Meaning & Personality Type Differences

The Big Picture of Human Psychology: Novelty, Stability, Flow & Wisdom

AC Harper says

Thank you for this post. It encouraged me to go back and re-read The INTP Quest which I bought 5 years ago. *This time* I found the book, particularly the last part, far more meaningful. I guess you have to be in the right place for the teacher to come.

A.J. Drenth says

You’re welcome AC. I’m happy to hear you found the post and the INTP Quest book meaningful.

Sam Estrada says

Great article, thanks!

A.J. Drenth says

You’re quite welcome Sam. Thanks for taking the time to comment.

Alex says

Very helpful!

A.J. Drenth says

Thanks Alex. Glad you enjoyed it!

Julie Tara says

Thank you so much for a wonderful article A.J. – and so timely as I just decided to become a Flow State Specialist and am studying it online! This is because I love Flow so much myself, finding it in my first career with ballet, then with building teams in business, and now with writing and video podcasts. I’m even trying my hand at painting and piano – I notice that, in both, I love the feeling of the activity itself in my body even more than the result.

I am an INFP and so find Flow primarily in solo activities, but then again, the group Flow state is pretty fabulous too. (I am about 60% Introvert to 40% Extrovert, so perhaps this is why I enjoy doing both.) Of course there are times when I just can’t find the entry points, so I want to learn the triggers well, so that I can be more conscious of how to get into Flow, as it’s so incredibly rewarding once I’m immersed. If I can then learn how to help others to access it too, well I’ll be thoroughly delighted!

Thanks again!

A.J. Drenth says

Thank you so much Tara for sharing your comment and experiences with flow. I think’s it great that you’re becoming a Flow State Specialist so you can help others better cultivate flow in their lives.

Dan says

I’ve been dripping and seeping for so long I forgot flow even existed. Thanks for unclogging me! I am inspired to check out the online course now.

Allen Robins says

Once again another beautiful and helpful article.

I love your closing thought “Ironically, we seek to understand ourselves with the ultimate aim of losing ourselves which, in turn, helps us feel better about ourselves. Ah, the wonders of human existence!”

I have read this idea and contemplated it at least a 1000 times over my life but it was not until I experienced it through deep meditation that I came to really understand that losing ourselves is finding ourselves. In reality you lose nothing but gain everything.

I also found these two insights helpful:

“Flow conforms to the laws of momentum. The more frequently we experience flow in a certain context, the greater the speed and likelihood of its future recurrence. If flow is essentially a brain state, building momentum through effective habits paves and substantiates flow-pertinent pathways”

“… we must be willing to weather psychological storms before a calm and steady flow state finally sets in. At times, these “storms” can be consciously quieted through various techniques and strategies; but not always. Just as often, flow comes as a result of patience, persistence, and a sense of optimism. ”

Paradoxically, growth and flow appear to come from the intertwining of great effort and struggle with that of an equal great letting go.

Again, thanks for sharing your insights. It has helped bring some clarity to some of my own flow experiences.

Happy Holidays

A.J. Drenth says

Great thoughts Allen. I really liked your point about flow emerging from an “intertwining of great effort / struggle and great letting go.”

Jeff Fermon says

Quality content as always A.J., thank you. I especially appreciated this part:

“Flow conforms to the laws of momentum. The more frequently we experience flow in a certain context, the greater the speed and likelihood of its future recurrence. If flow is essentially a brain state, building momentum through effective habits paves and substantiates flow-pertinent pathways.”

As an INFP, something that’s intrigued me regarding my own flow is how even my extraverted functions are employed inwardly. There may be some external inputs like music or physical accompaniment like walking or pacing, but it’s as if everything is employed in service of creating optimal conditions for my mind to simply flow in deep internal contemplation.

Interestingly, it’s not just an Fi – Si loop. Ne is extremely active and engaged in the process of both creating and adapting ideas while Te sorts through, organizes, and performs various operations on all the raw ideation. Si can be an invaluable archive and a foundation for experiential reference but getting too comfortable in its familiar grooves puts me at risk of ossifying in its amber resin. All the while, Fi floats upon the rafts of ideas and acts as a rudder steering the process depending on its moods and desires and its neurotic habits and coping mechanisms.

I’m often vulnerable to having Ne hijacked to reexamine something, sometimes indefinitely. Entire flow sessions can be fruitlessly squandered in this manner. I’ve gone so far as to wear a beaded bracelet as a sort of talisman to remind me to break out of my imagination and reestablish presence in more mutually shared realities.

It can take a lot of effort and some sacrifice to emerge from these inner flows and transition toward a more outward locus. Crossing hemispheres so that Te can at least have a chance to fulfill its executive duties can deplete me rapidly when my “actualization fitness” has lapsed due to introverted neglect. But it can also lead to the most rewarding flow states of all: those from which I can bring something of possible value into the world.

Harsh Rajput says

I think what religious teachers describe as “union to God” is a flow state which resulted from being engaged in prayer for long times.