As discussed in my latest book, The INTP Quest, INTPs can be seen as searching for two primary things: purpose and wisdom. With respect to the former, they strive to clarify their identity and role in the world. They seek a purpose that furnishes a reliable stream of meaning and inspiration. At the same time, INTPs recognize the importance of balance, wisdom, and self-development, all of which are prerequisites for finding peace with themselves and the world around them.

One way INTPs advance in their quest is by exploring the paths taken by other INTPs, including those who have achieved great eminence. In this post, I will offer snapshots of 12 famous INTPs, which can provide us with a sense of the INTP’s vocational options, as well as the potential benefits and challenges associated with each. These case studies can also key us into some of INTPs’ core existential difficulties and point they way to possible solutions.

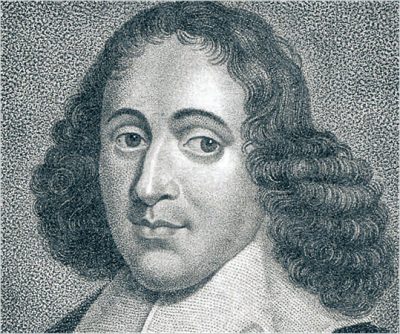

1. Spinoza

“Nothing in the universe is contingent, but all things are conditioned to exist and operate in a particular manner.” —Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza is typically characterized as a Rationalist philosopher. Spinoza’s rationalism was epitomized in his most famous philosophical work, Ethics. He begins by laying out his philosophical foundation with a handful of first principles and then proceeds to deduce much of the remainder of his philosophy from those principles. Showing little interest in empiricism (S), metaphor (N), or feeling-based (F) arguments, Spinoza’s structured approach is clearly rooted in thinking (T), or more particularly, Introverted Thinking (Ti).

The apparent dominance of Ti in Spinoza’s thought is explainable in terms of both his culture and disposition. At the time of his writing, neither Hume nor Kant had offered their critiques of knowledge and reason. This, combined with burgeoning enthusiasm for Enlightenment rationalism, gave Spinoza the “green light” for unfettered use of Ti.

Of course, much has changed for INTPs since the time of Spinoza. No longer is it en vogue to construct a philosophy based strictly on first principles and deductive reasoning. Empiricism and critical thought have gained much traction in our cultural mind over the last few centuries. Despite this, most INTPs still possess a sort of “inner Spinoza” that would relish constructing a rational system akin to what we find in Ethics. But it is also true that INTPs can’t entirely ignore their current historico-cultural situation, which warns of the shortcomings of purely a priori, deductive philosophies.

Although it is true that all INTPs have an inner Spinoza that we call Ti, there is another part of them that feels dissatisfied with, and even disenchanted by, grand philosophical systems that seem to leave little room for ongoing exploration and creativity (Ne). INTPs’ concerns about ideational closure may inspire them to rebel against rational systems, perhaps even against those they’ve constructed, as a means of reopening the door to unfettered ideation. Put another way, they fight against the structuring impetus of Ti in order to liberate their auxiliary function, Extraverted Intuition (Ne).

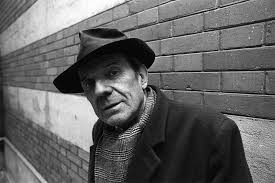

2. Deleuze

“Art, science, and philosophy are neither contemplative, reflexive, nor communicative. They are creative, that’s all.” —Deleuze

In the works of the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, one can witness his inner struggle between order (Ti) and novelty (Ne). On the one hand, we find Deleuze crowning the Spinoza as the “Christ” and “prince” of all philosophy, which is clearly a nod to Ti, while on the other, we see him eulogizing the schizophrenic state, which he viewed as the quintessence of freedom and creativity (Ne). His rebellion against Ti is also evidenced in the lack of logical consistency and coherence in several of his works, which many scholars presume was intentional, as well as in his claim that philosophy is not about knowledge or truth (T), but about the “Interesting, Remarkable, and Important.”1 Deleuze also showed great admiration for artists and novelists, such as Proust, who embodied the sort of unrestrained Ne he fancied.

For Deleuze, the hallmark activity of the philosopher (or perhaps more accurately, the INTP philosopher) is the creation of concepts. In the concept, Deleuze finds a perfect medium for the marriage of structure (Ti) and openness (Ne). A concept is distinct and solid enough to satisfy Ti’s need for discriminating, classifying, and ordering, while at the same time fluid and permeable enough to permit multiple or intersecting meanings (Ne). The INTP philosopher’s penchant for versatile or polyvalent concepts finds its contrast in the approach taken by Te scientists, who insist on terminological strictness and univalence of meaning so as to avoid ambiguity. In Deleuze’s view, such rigidity is unwelcomed by the philosopher, who feels compelled to connect his work to the chaotic, mysterious, or metaphysical (Ne) element of reality, or what he called “the infinite.”

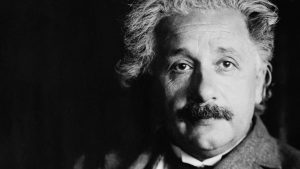

3. Einstein

“The true sign of intelligence is not knowledge but imagination.” —Einstein

Einstein was not your typical scientist. In many respects, he operated more like a speculative philosopher than a scientist, as exemplified in his frequent use of “thought experiments.” We should thus abstain from applying Deleuze’s portrayal of scientists to Einstein, as it was really aimed at TJ rather than NTP scientists.

Similar to Deleuze, one can discern a salient Ti-Ne tension in Einstein’s psychology. On the one hand, he insisted that “God doesn’t play dice” (Ti), while on the other, he claimed that “the most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious” (Ne).

Among Einstein’s more notable INTP features was his obsession with wrestling with abstract problems that captured his interest. In particular, he strove to understand the fundamental nature of the universe, which would reveal “the mind of God.” While many INTPs lack Einstein’s level of interest and talent for physics, they may exhibit a similar voraciousness for solving abstract problems that strike them as important, interesting, or meaningful.

At least from a psychological perspective, it was probably fortunate for Einstein that he never fully solved his primary problem of interest. While he obviously made a number of groundbreaking discoveries, he never achieved his ultimate goal of producing a tenable unified theory. Although his failure in this respect was clearly a source of frustration for Einstein, the dream of a unified theory nonetheless served as a powerful source of inspiration and motivation throughout his life.

As I discuss in The INTP Quest, INTPs who do manage to solve their most cherished abstract problems may struggle to find suitable replacements. Like a dog that finally catches its own tail, they may find themselves strangely dissatisfied, unsure of what to do next. While they may try in earnest to identify a new and equally compelling problem, many sense that nothing can match the passion generated by their original problem of interest. It may thus take them years to find their way to a sufficiently satisfying substitute. And this is why Einstein’s inability to produce a unified theory may have ultimately been to his benefit.

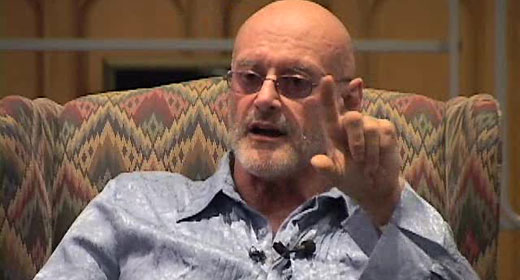

4. Ken Wilber

“The ultimate metaphysical secret is there are no boundaries in the universe. Boundaries are illusions, products… of the way we map and edit reality.” —Ken Wilber

Ken Wilber is a contemporary thinker and author, best known for his contributions to transpersonal psychology and integral theory. In his first book, The Spectrum of Consciousness, which he published at the ripe age of 23, Wilber placed his philosophical bets on the metaphysics and practical benefits of Eastern mysticism. He also advanced a sweeping narrative of the evolution of Spirit, following the general trajectory of thinkers like Hegel and Teilhard de Chardin.

Wilber’s work is not only concerned with the True (T), but also the Good (F). This of course should not surprise us, as this is how the majority of INTP philosophers unwittingly attempt to marry their dominant Ti and inferior Fe functions. More specifically, they hope to eventually arrive at an understanding of what is good by first determining what is true. Once they feel they have a good sense of both, they set out to enlighten others. Not only did Wilber strive to enlighten others through his prolific writing efforts, but he also founded an educational training center—The Integral Institute—as a means of furthering his work and mission.

Again, some INTPs may find it difficult to understand how an INTP could feel so confident in his ideas that he would be compelled to write countless books, let alone establish an institute. It may be that genius-level INTPs, such as Wilber or Chomsky, are more apt to reach this level of confidence and certainty than others are. At the same time, we can find equally brilliant INTPs, such as Deleuze, who remained quite open and explorative (Ne) throughout their careers, eschewing the siren call of philosophical closure (Fe).

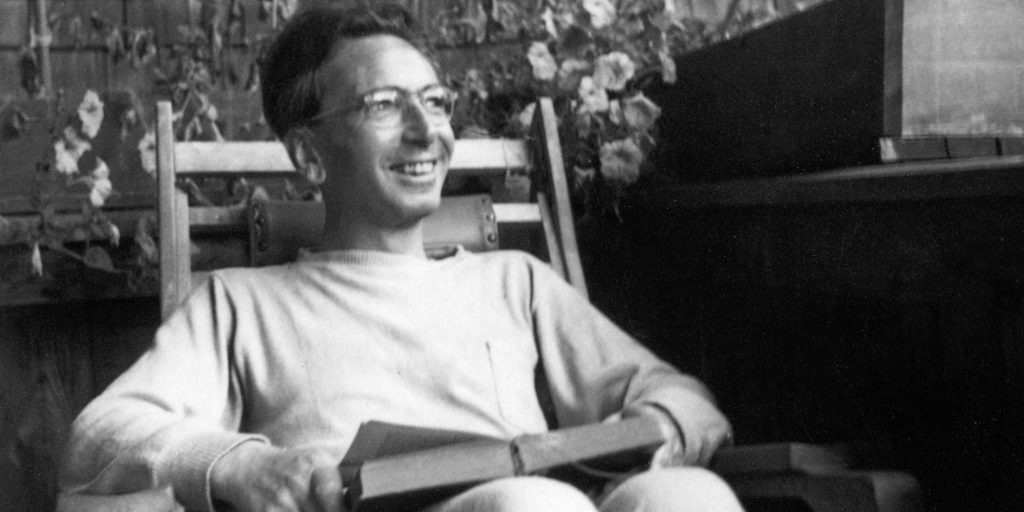

5. Viktor Frankl

“Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation of his life” —Viktor Frankl

Best known for his work, Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl was a psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor. His book’s title could in many respects serve as the INTP anthem, which in typological terms could be translated: “INTPs’ Search for Fe.” The combination of Ti skepticism and inferior feeling makes INTPs far more preoccupied with the problem of meaninglessness or nihilism than other types. To combat this fear, they embark on what is often a lifelong quest for meaning and purpose. As an INTP, Frankl was no different. He claimed that it was his hope in meaning (Fe) that pulled him through the countless horrors of the concentration camps. He would later write: “Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation of his life…Man is able to live and even die for the sake of his ideas and values.”

Building on his beliefs about the centrality of meaning in human life, Frankl developed a meaning-centered psychotherapeutic approach that came to be known as logotherapy. Thus, like many INTPs, we find in Frankl and desire to apply, disseminate, and immortalize his ideas.

6. Robert Pirsig

“Want to make the perfect painting? Perfect yourself then paint naturally.” —Robert Pirsig

Robert Pirsig entered the public eye with his mid-life publication of what is now considered a classic philosophical novel, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which traced his own philosophical journey in an instructive yet entrancing way. The book culminates with Pirsig’s discovery of his ultimate philosophical concept—Quality—which was sufficiently broad and versatile to accommodate truth and meaning, art and science, beauty and technology, thinking and feeling.

Pirsig’s book is an apt portrayal of the INTP’s quest for foundational concepts. We encountered this earlier in Deleuze’s notion of the philosopher as concept creator. For many INTPs, the search for meaning is in many respects a search for the right concepts. Not only that, but INTPs tend to be drawn to similar concepts, such as meaning (Frankyl, Tillich), spirit (Hegel, Wilber), freedom (Bergson, Hegel, Snowden), mystery (Einstein, Tillich), and creativity (Bergson, Deleuze).

I should also mention that for Pirsig, Quality was not just a concept, but a way of life; it was not merely an expression of the True, but also of the Good. Indeed, it would be a rare INTP who could fully separate these things, as INTPs seem naturally disposed to extrapolating what should be from their understanding of what is. While many commence their philosophical journey with metaphysical investigations (Ti-Ne), their interest typically migrates toward moral philosophy (Fe). Of course, this is typologically consistent with the respective ordering of their four functions: Ti-Ne-Si-Fe.

Despite INTPs’ shared concern for the True (T) and the Good (F), most realize that their ability to achieve F certainty can only come through consistent employment of T reasoning, not the other way around. Unlike F types, that can’t authentically discern truth through feelings (Fe), but must rely more heavily on reason (Ti), intuition (Ne), and experience (Si). They thus see their first objective as cultivating their Ti grounds, which they hope will ultimately give rise Fe understanding. This process is at the heart of Pirsig’s book, demonstrating how NT investigations can lead to an understanding of “how to live” (SF).

7. Bill Gates

Bill Gates took a rather different path from the INTPs described thus far. Rather than questing for philosophical or scientific truths, he devoted his life to technological innovation. At first blush, innovative work may seem a purer form of T activity than philosophizing, as the latter is often underpinned by moral concerns (Fe). Moreover, since innovation doesn’t aim to discover a static set (J) of truths, it seems more open-ended (P) than philosophizing. One might therefore argue that INTP innovators are at lower risk for getting tripped up by their inferior Fe function. They may also be less susceptible to running short on interesting projects, since the creative possibilities for new technologies are effectively infinite.

With that said, no INTP can fully escape the influence of Fe. Gates was undoubtedly aware of the power and fame (Fe) that a successful enterprise could procure—the extraverted rewards for introverted brilliance. We might therefore pause before concluding that INTP innovators are somehow exempt from the challenges of the type problem. My suspicion is that INTP innovators wrestle with the ethical implications and ultimate value (Fe) of their work more than we know.

8. Canguilhem

Georges Canguilhem was a 20th-century historian and philosopher of science. While becoming an historian may at first sound like a commitment to empiricism (S), it actually affords more room for subjectivity than one might think. In the words of Canguilhem: “The historian of science has no choice but to define his object. It is his decision alone [Ti] that determines the interest and importance of his subject matter.”2

Like many INTPs, Canguilhem’s interests revolved around the exploration of concepts:

“Canguilhem has a clear predilection for a history of concepts, a history of problems meandering through the historical space of the sciences. While he talks about scientific objects, it is mainly concepts which he addresses…Canguilhem was a master of conceptual landscape painting.”3

As discussed in The INTP Quest, historical inquiry allow INTPs to explore their interests in both concepts (Ti-Ne) and people (Fe), and to do so in a way that is more open-ended (Ne) than the philosopher seeking THE truth. For the INTP historian, truth is always in flux, emerging from the needs and desires of a particular culture at a particular time in history. The historian’s task then, is to write (and re-write) stories about ideas and culture that help us understand where we’ve been and, just as important, where we might be headed.

Personality wise, the openness of the historian resembles that of the innovator. Since there is no final interpretation of history, there is always more to be explored. This can be reassuring to INTPs who might otherwise be concerned about there being a limited supply of meaningful ideas for them to explore. Shifting their sights away from eternal truths and toward relative / historical truths can reveal new paths for Ne exploration.

The historian (especially the NP historian) tends to eschew dogmatism, perhaps sensing that the glory associated with ultimate answers is illusory and incapable of satisfying his ongoing appetite for novelty. In contrast to INTPs who are desperate to find answers (Fe), historians manage to curtail that impulse in order to savor the rewards of open-ended exploration (Ne). While the historian cannot completely eliminate the effects of Fe, he understands how to integrate it in such a way that it doesn’t interfere with, or prematurely truncate, the explorative process.

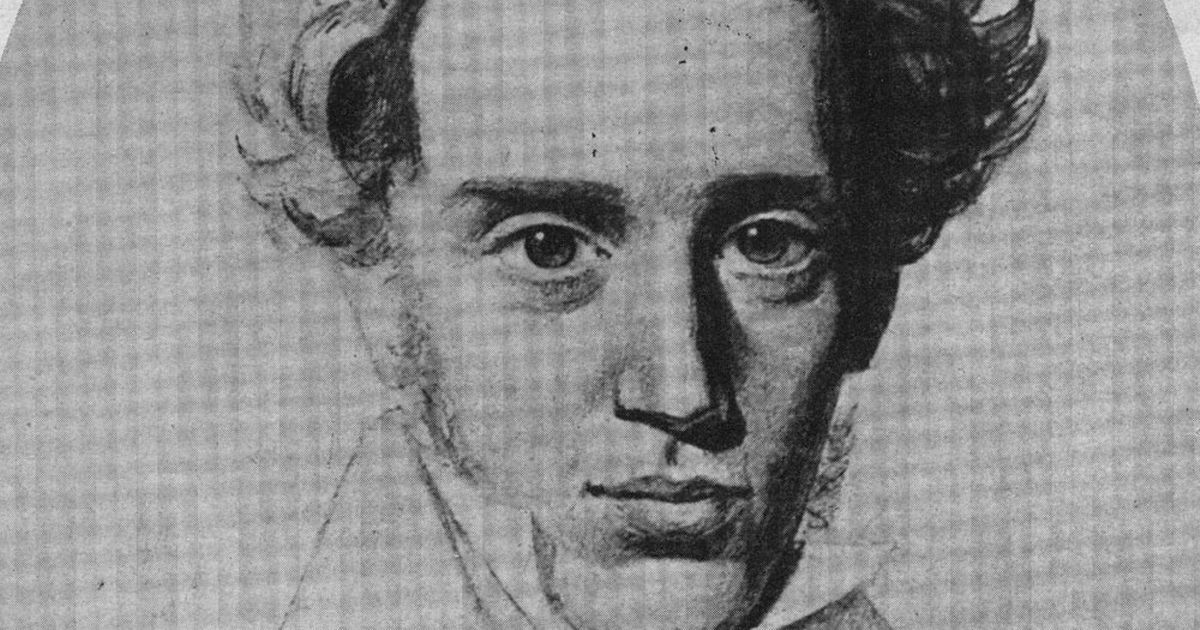

9. Kierkegaard

“Pleasure disappoints, possibility never.” —Kierkegaard

Many type enthusiasts have cast Kierkegaard as an INFP, most likely because of his poetical style, melancholy demeanor, propensity for sentimentalism, and rejection of philosophical rationalism. However, there are features of his personality and writings, as seen in Either/Or and Concluding Unscientific Postscript, that suggest he may have been an INTP. For instance, in Either/Or Kierkegaard proffers thoughts and observations on how to live well, many of which look a lot like Ti principles and disciplines. In addition to his advice to abstain from marriage and close friendships, he suggests: “One ought to devote oneself to pleasure with a certain suspicion, a certain wariness…One should keep the enjoyment under control, never spreading every sail to the wind…” He also espoused the “principle of limitation: the more you limit yourself, the more fertile you become in invention.” These and other characteristics led Thomas M. King, author of Jung’s Four and Some Philosophers, to type Kierkegaard as an INTP. Regardless of whether Kierkegaard was in fact an INTP or an INFP, these two types share enough structural similarity (i.e., an introverted judging function followed by Ne & Si) that studying his life and work can prove instructive for INTPs.

An existentialist at heart, much of Kierkegaard’s work was devoted to exploring methods for optimal living. As for many INTPs, he viewed boredom as the arch enemy and was constantly experimenting with ways of keeping life fresh and interesting. Like Deleuze, he was keenly aware of the potential oppressiveness of excessive philosophical structure, which inspired him to rail against grand philosophical systems (e.g., Hegel’s philosophy) and to champion the virtues of individuality and subjectivity.

In emphasizing novelty (Ne) over structure and objectivity (T/J), Kierkegaard is less like Spinoza, Kant, and Wilber and more like the innovators and historians we’ve reviewed. He saw closed philosophical and religious systems as toxic to Ne, and to his mind, Ne was a critical feature of the good life: “If I were to wish for anything, I should not wish for wealth and power, but for the passionate sense of the potential…for the eye which sees the possible. Pleasure disappoints, possibility never.”

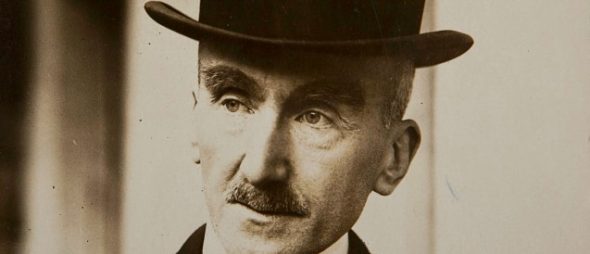

10.Bergson

“The role of life is to insert some indetermination into matter.” —Bergson

Henri Bergson was a brilliant French philosopher who came to be known for his spiritualist / vitalist sympathies. Like many INTPs, Bergson was effectively a pantheist. He saw the evolution of life as animated by a universal mind / spirit / life force (a.k.a., the “élan vital”) as enumerated in his classic work, Creative Evolution.

Bergson’s thought exhibits important parallels with that of Pirsig. Namely, his concepts of Duration and Intuition connote something similar to Pirsig’s notion of Quality. Bergson went to great lengths to enumerate the differences between quantitative / scientific time and what we might call lived time (i.e., Duration). In his view, our failure to understand how lived time differs from quantitative time has contributed to our inability to understand the role of mind / spirit in the evolution of life. For it is in lived time that some measure of freedom / indeterminacy exists and only there can real change / evolution occur. Bergson saw lived time as the birthplace of creativity, both on an individual and evolutionary level. Like many INTPs, he envisioned substantial overlap between the mind-spirit of the individual and that of nature / the universe as a whole.

Insofar as Bergson was a vitalist and espoused a specific method (i.e., Intuition), one could label him a dogmatist. But when we consider his emphasis on spirit, creativity, and freedom, it is clear that he placed immense value on openness and novelty (Ne). Like many of our aforementioned INTPs, he was careful to ensure that the philosophical and creative freedom of Ne was preserved in both theory and practice.

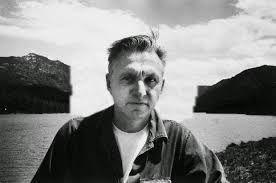

11. William Barrett & 12. Thomas M. King

William Barrett was a philosopher with a particular interest in existentialism, as showcased in his classic work on the subject, Irrational Man. Thomas M. King, a self-professed INTP, was a priest and professor of theology at Georgetown. While King wrote broadly on both religion and philosophy, several of his works were devoted to the exploring the life and work of Teilhard de Chardin.

I decided to pair these two thinkers because of notable similarities in their vocational activities. Namely, neither Barrett nor King was concerned with advancing a philosophy of his own. Both preferred to work as expositors rather than independent theorists. King immersed himself in the works of Teilhard, while Barrett inhabited the realm of existentialists such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Heidegger.

Expositors can enjoy a great deal of creative and interpretive leeway, even more so than historians, especially when writing for a general audience or exploring the works of multiple thinkers. Not only are they free of any obligation to produce a carefully structured or systematic philosophy of their own, but they can also enjoy the luxury of bringing their own perspective to a given topic or a thinker. One can therefore see why expository writing might serve as an attractive and satisfying vocation for INTPs.

Famous INTPs: Closing Remarks

In response to my recent left vs. right brain post, a blog reader remarked that, in his experience, INTPs were paradoxically “more left-brained” AND “more right-brained” than most other types. I found this observation both astute and intriguing. On the one hand, INTPs are strongly driven to understand the fundamental nature of things (e.g., “God doesn’t play dice.”), while on the other, they are among the most open-minded and ideationally creative of the types. Not only does this psychological admixture make the INTP a rather complex and fascinating personality type, but it also sheds light on this type’s particular existential challenges.

While INTPs, like other types, must find ways of reconciling their dominant (Ti) and inferior function (Fe), they also face what may be an even greater challenge, that of simultaneously satisfying their need for order / structure (Ti) and openness / novelty (Ne). Deleuze seemed as cognizant of, and conversant with, this problem as any philosopher. Other INTPs have been less conscious of this problem, but have unwittingly dealt with it in various ways.

It has not been my intention to propose a “one size fits all” solution to INTPs’ existential challenges. Clearly, INTPs find different ways of satisfying their typological needs in accordance with their own psychocultural situation, phase of development, and so on. In some respects, knowing what works best requires a fair amount of personal experimentation. At the same time, INTPs can greatly benefit from the insights of personality typology, which help them understand the deep structures and dynamics of their type.

Learn More in Our INTP Book:

Learn more about INTPs—their personality, careers, relationships, cognition, life struggles, and more—in our INTP book (the #1 INTP book on Amazon with over 300 reviews):

The INTP: Personality, Careers, Relationships and the Quest for Truth & Meaning

#1 INTP Book

on Amazon

#1 INTP Book

on Amazon!

Related Posts:

INTP & INFP Identity-Seekers & Creatives

Notes:

1. Deleuze, G & Guattari, F. What is Philosophy? 1994.

2. Delaport, F. A Vital Rationalist: Selected Writings from Georges Canguilhem. p. 28.

3. Gutting, G. Continental Philosophy of Science. p. 193.

MG says

Hi AJ,

Thanks for this great post! By reading it, we can feel the NE open-mindedness of (your) INTP personality. Your article has made me think that the absolute way of conciliate order (TI) and open-mindedness (NE) for an INTP is to accept the World as it is, I mean conceiving the right order (TI) is accepting the infinity/diversity/mistery (NE) of the world, as a Whole. Thus an INTP (or any individual who are in the process of acceptance of this Truth) becomes a merely creative observer of the World and the Life, who keep striving to the process of enlightenment (for both us and the population). No doubt is the way followed by many of individuals you reviewed.

Thanks again.

INTP technologist says

Interesting to Type famous personalities just by their thoughts, however generally I find it more reliable to look at how they behave in their personal life, especially before they became famous.

Also on INTP technologists having Fe struggles isn’t something I see in my experience in the field, and knowing other INTPs who work in it. Every thing you do in this work is for people, if it wasn’t you wouldn’t be doing it. Fe satisfaction is the least of our troubles.

Otherwise excellent article, as usual.

Jill says

Great article–I’ve shared the article with my friends. I especially like the discussion of INTP being the most left brain AND most right brain–clarifies the conundrum I’ve had with clarifying myself.

Brad Hendricks says

Tina Fey is an INTP so that would be interesting to see Dr. Drenth’s perspective. I agree with Ken WIlber. I have been studying him since the 1990’s and find a kindred spirit. Only later did I connect him to my INTP.

Suzyyne says

I love your in depth analysis of types. Your previous article about the INFP inferior Te function enlightened my paradigm. I still have a hard time explaining to this part of me that Fi and Ne are my strenghs, though I value Te.

Please, write a book and similar article for INFP.

Help me quiet the disappointed Te that won’t believe creative art and storytelling have value in my vocation. Thank you !

Sarah says

As a female INTP myself, it would good to have the female perspective on this type represented. I believe Marie Curie was an INTP..

N. W. says

A.J. ,

I am humbled (and pleased) that you used my observation in this article (i.e. the first sentence of Closing Remarks). At the time I made the comment I thought of it as being something merely from my own experience; but I can’t say I know any other INTP’s in real life, so it’s nice to know I’m not the only one after all.

Incidentally, a really good example of this — and maybe someone you’d consider writing on in the future qua another famous INTP — is Blaise Pascal.

A.J. Drenth says

Thank you N.W. for the great observation. I think it rang true for a lot of INTPs.