Sex differences in personality and temperament have been documented in many empirical studies. In most mammalian species, including humans, males tend to be physically larger, more aggressive, dominance-oriented, risk-prone and exhibit lower investment in offspring than females. According to Sergey Budaev’s paper, “Sex Differences in the Big Five Personality Factors,” there is “no doubt that we have evolved in the context of major activities which influenced the fitness of our ancestral species, such as social dominance, social exchange, and mate choice.” In particular, there are greater incentives for males to compete for rank and status within social hierarchies, which presumably creates more opportunities for economic and social rewards, as well as reproductive success.

Even those who consider evolutionary accounts of gender differences to be overly simplistic can nonetheless appreciate the utility of terms like “masculinity” and “femininity.” Irrespective of their foundations—i.e., whether they are ultimately more nature or nurture based—the fact remains that these long-held, archetypal concepts tell us a lot about human personality. Moreover, regardless of what gender we identify as, we will have traits that are perceived as more masculine or feminine.

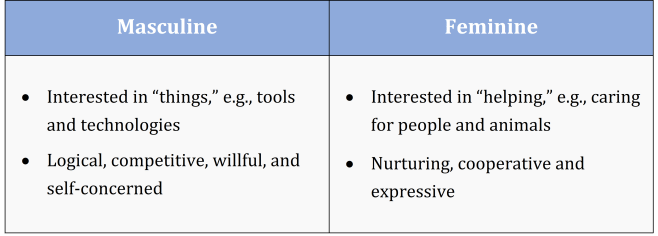

Although we all have our own preconceived notions regarding what constitutes masculine and feminine, for our purposes here, it will be useful to define them. To help us do so, we will consult a seasoned personality researcher, Richard Lippa, whose work explores the intersection of sex, gender, personality and interests.

In his article, “On Deconstructing and Reconstructing Masculinity – Femininity,” Lippa argues that gender differences be conceived in light of two well-established theories: John Holland’s “RIASEC” model of career interests and Colin DeYoung’s Interpersonal Circumplex model. In particular, Lippa suggests that Holland’s “Realistic” interest domain—associated with an interest in working with “things” (e.g., tools, technology)—and the “Social” domain—involving an interest in helping people (e.g., teaching, nursing)—can serve as handy snapshots of masculine and feminine interests respectively. This aligns nicely with my post, Cognitive Styles of Thinkers (T) vs. Feelers (F): Visual, Spatial & Verbal, where I provide evidence that masculine and feminine interests manifest as early as infancy, taking the form of attention to objects and motion (rudimentary “physics” if you will) versus interests in human faces and imaginative doll play (rudimentary “psychology”). These aptly correspond with Holland’s “things” versus “people” dichotomy.

The second theory recommended by Lippa, the Interpersonal Circumplex (IPC) model, is rooted in the Big Five. But since we will soon be discussing the Big Five in greater depth, we will settle for Lippa’s synopsis of the IPC model. In the aforementioned paper he suggests that the IPC model understands masculinity in terms of dominance (or equivalently, instrumentality or agency) and femininity as nurturance (or equivalently, communion or expressiveness). Dominance / instrumentality can be understood as willful self-interest, competitiveness, and independence, while nurturance / community involves a greater concern for, and affiliation with, others.

Taken together, these theories offer a good overall picture of the major components of masculinity and femininity, as depicted here:

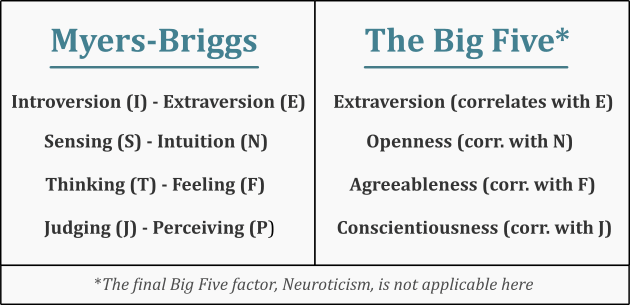

Having now outlined our working definitions of masculine and feminine characteristics, we can proceed to our next task, which is understanding how and where these important personality traits are incorporated into the Big Five and Myers-Briggs taxonomies. Before doing so, however, I’d like to remind readers of the significant conceptual overlaps and correlations between these two personality frameworks:

Masculine & Feminine in the Big Five

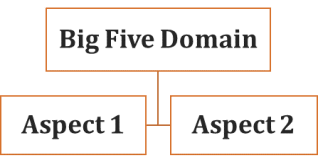

To organize and inform our discussion of the Big Five, we will draw on a key paper by Weisberg and colleagues: Gender Differences in Personality Across the Ten Aspects of the Big Five. As enumerated in the paper, each of the Big Five domains is composed of two subcategories called aspects:

The two aspects of each domain tend to correlate and co-occur, which is why they are conceptually paired under a single domain in first place. However, in many cases, men score higher on one aspect and women on the other, which can clue us into how the Big Five incorporates the masculine and feminine. We’ll now examine each of the Big Five domains and their respective aspects, including how they reflect masculinity and femininity.

Big Five Extraversion

The two aspects of Big Five Extraversion are Assertiveness and Enthusiasm. According to Weisberg’s paper, males generally score higher in Assertiveness—which is characterized by higher levels of activity, boldness, achievement, and excitement-seeking—and females in Enthusiasm—involving higher levels of warmth, gregariousness, positive emotions, and social closeness. We might say that masculine individuals approach social situations with an eye toward dominance, influence, and social status, whereas more feminine persons do so for the sake of enjoyment and a sense of social closeness. To summarize:

Assertiveness: More Masculine.

Enthusiasm: More Feminine.

Openness to Experience

The two aspect of Openness to Experience are Intellect and Openness. In his paper, “Between Facets and Domains,” Big Five researcher Colin DeYoung asserts that Intellect “encompasses intellectual engagement with abstract and semantic information.” Here are some questionnaire items designed to assess Intellect:

- “I am quick to understand things.”

- “I enjoy philosophical discussions.”

- “I like to solve complex problems.”

Openness, according to DeYoung, “reflects engagement with perceptual and aesthetic domains, artistic interest and fantasy proneness.” It can be useful to associate Openness with the perceptual realm, and Intellect with the conceptual realm. Here’s a sample of Big Five Openness items:

- “I see beauty in things that others might not notice.”

- “I daydream often.”

- “I have a vivid imagination.”

Research indicates that men tend to score higher in Intellect (which, by the way, is not synonymous with IQ) and women in Openness. For a fuller discussion of this topic, check out my post, Myers-Briggs Intuition through the Lens of Big Five Openness / Intellect.

Intellect: More Masculine.

Openness: More Feminine.

Agreeableness

The two aspects comprising Agreeableness are Compassion and Politeness. Considering that Agreeableness corresponds to Myers-Briggs Feeling (F), it’s unsurprising that it correlates substantially with femininity. Unlike the Big Five domains we reviewed thus far, women generally score higher in both aspects of Agreeableness, suggesting that Compassion and Politeness are associated with femininity. According to Weisberg’s paper, this may stem from gender differences in self-construal:

“Men tend to have an independent self-construal, or a sense of self that is separate from cognitive representations of others. Women have a more interdependent self-construal, in which their sense of self includes others.”

Compassion: More Feminine.

Politeness: More Feminine.

Conscientiousness

The two aspects of Conscientiousness are Orderliness and Industriousness. The former reflects traits pertaining to maintaining order and organization, including perfectionism. According to Weisberg’s paper, females generally score higher in Orderliness.

Industriousness incorporates traits like efficiency, perseverance, and achievement-striving. In Weisberg’s study, men scored higher than women in Industriousness. If masculinity involves competitiveness and a strong desire for self-distinguishment, this finding is not all that surprising.

Orderliness: More Feminine.

Industriousness: More Masculine.

Neuroticism

The two aspects of Neuroticism are Withdrawal and Volatility. Women have been found to experience higher levels of negative emotions including anxiety, depression, and self-consciousness—all of which relate to the Withdrawal aspect.

Volatility references the frequency and intensity of changes in mood and emotions. Although women often score higher in Volatility, when Withdrawal characteristics are controlled for, their levels resemble those of men. Irritability and quickness to anger are also included under Volatility, both of which are common in men.

Withdrawal: More Feminine.

Volatility: No significant difference.

Masculinity, Femininity & the Myers-Briggs / MBTI

It’s now time to switch taxonomies and see how the Myers-Briggs / MBTI handles the masculine and feminine dimensions of personality. Although the Myers-Briggs doesn’t utilize aspects like the Big Five, the MBTI Step II delineates five facet scales for each dichotomy, which we will periodically reference in our discussion:

Extraversion (E) – Introversion (I)

As we’ve seen, the Assertiveness aspect of Big Five Extraversion is characteristically more masculine, and Enthusiasm more feminine. If we look at the five facets of MBTI Extraversion, we discover that it has a fairly similar structure, with two facets corresponding to Assertiveness (Initiating, Active) and three to Enthusiasm (Expressive, Gregarious, Enthusiastic).

I find this interesting because many people, when discussing MBTI Extraversion (or extraversion generally), tend to focus almost exclusively on its sociability (i.e., Enthusiasm) component. However, they often overlook, or remain impervious to, its Assertiveness element.

Sensing (S) – Intuition (N)

Of all the Myers-Briggs dichotomies, Sensing and Intuition appear to be the least related to masculinity and femininity. Granted, we could point to facets that, in light of our earlier discussion of Openness to Experience, are somewhat more feminine (e.g., imaginative) or masculine (e.g., conceptual). That said, the S-N dichotomy may in fact be more gender neutral than Openness to Experience, which leans more heavily toward the feminine (i.e., females score higher in four of six Openness to Experience facets). Despite this, the general population is still apt to conceive Intuition as a feminine quality (e.g., a “woman’s intuition”). Those taking the MBTI will thus require education regarding its special meaning within the model, including its role in theoretical and conceptual types of cognition.

Thinking (T) – Feeling (F)

Similar to Big Five Agreeableness, the Thinking – Feeling dichotomy represents the most significant gender category of the Myers-Briggs, with Feelers exhibiting more feminine traits and Thinkers more masculine characteristics.

One advantage of the MBTI over the Big Five is its inclusion of a “logical – empathetic” facet, which nicely corresponds to Holland’s “things – people” dichotomy. Although the Big Five clearly incorporates empathy under Agreeableness, it curiously excludes any mention of logical / analytical thinking, opting instead for negative descriptors like “hard-hearted.” By contrast, the Myers-Briggs allows for a “head” (T) – “heart” (F) conception that immediately resonates with people in a way that “Agreeableness” doesn’t.

Judging (J) – Perceiving (P)

Myers-Briggs Judging (J)—whose facets include systematic, planful, early starting, scheduled, methodical—is closely related to the Orderliness aspect we explored under Big Five Conscientiousness, which women tend to score higher on. This may explain, at least in part, why over 56% of females test as J types.

Unfortunately, Myers-Briggs Judging seems to lack an effective masculine analogue, such as Industriousness, to balance it out. Granted, Judgers are commonly conceived as hard workers, goal-oriented, and persevering. In other words, people tend to see them not only as Orderly, but also Industrious. It’s too bad that more of these characteristics haven’t been explicitly integrated into the Judging facets. Perhaps the issue stems from the fact that Perceiving traits, such as “open-ended” and “spontaneous,” aren’t precise opposites of Industriousness. However, one could readily argue that Industrious persons working toward a goal are more focused and committed, and thus less open-ended. The MBTI might therefore consider incorporating more Industrious traits into its conception of Judging.

Learn More in Our Books:

My True Type: Clarifying Your Personality Type, Preferences & Functions

The 16 Personality Types: Profiles, Theory & Type Development

Related Posts:

Myers-Briggs Intuition through the Lens of Big Five Openness / Intellect

Cognitive Styles of Thinkers (T) vs. Feelers (F): Visual, Spatial & Verbal

Milk says

Great article in its address of gender and these type systems in addition to contrasting them more generally. Thanks

A.J. Drenth says

You’re welcome Milk. Thanks for your comment.

Leslie says

Im a female who can’t multitask. I can’t even concentrate on talking while driving. Music on the radio distracts me when I’m studying. I’m more like my male friends than my female friends in this respect. Does it have anything to do with me being an INTP?

A.J. Drenth says

Good question Leslie. Although I haven’t researched that issue thoroughly enough to answer your question, you might find this paper on multitasking helpful.